Chapters Thirteen to Eighteen having carried out the grand design of the Ground Floor, Miss Austen in these final chapters of Volume I now sets about sealing off this initial section, presumably from penetration and damage by the elements, as though a significant period of time is expected to elapse before unveiling the beginnings of the massive staircase which will lead from the Main Floor to the upper levels.

In the aftermath of Mrs. Bennet's loud and public vulgar boasting of her daughter Jane's certain approaching marriage to the eligible (which is to say single and rich) Mr. Bingley, the entire Netherfield party has left for London, seemingly never to return, thus closing off the most promising, obvious, and direct means for Jane Austen the architect to ascend to those higher levels of her Novel.

In my summary of a seemingly similar transition between Foundation and Ground Floor (Foundation (3):— Foreshadowing, or Moving Up), I pointed out that

... nothing at the end should be a surprise, because all in this Novel will have been anticipated in the introductory chapters, and can lead to no other conclusion.

And that

... Pride and Prejudice contains a great many characters and situations, none of them incidental or unimportant. And once the Novel attains the lofty upper reaches of that literary mansion, every personage on the lower level will have been given the means to support an impressive amount of weight upon his or her shoulders.

But here we are at the end of Volume I with completion of the Main or Ground Floor level in my system of architectural accounting, and we seem farther away from resolution than at any point since we started. And my blithe placement of one floor upon the other has hit an immoveable obstacle and come to a crashing halt.

Where are the hints at great treats in store, the foreshadowing, the palpable upward propulsion that made turning the pages of those earlier chapters a call to great adventure? Rather than anticipation, Jane Austen is here calling upon the reader to share in the general atmosphere of disillusionment and despair that closes Volume I.

In fact, the only anticipation is contained in Caroline Bingley's gleefully cruel letter to Jane predicting a forthcoming much-hoped-for marriage between her brother Charles Bingley and Georgiana Darcy, Mr. Darcy's young sister.

Chapter 21 has also seen the return of Mr. Wickham, who attaches himself particularly to Elizabeth while voluntarily acknowledging that the necessity of his absence had been self imposed.

'I found,' said he, 'as the

time drew near, that I had better not meet Mr. Darcy ... and

that scenes might arise unpleasant to more than myself!'

She heartily approved his forbearance, and they

had leisure for a full discussion of it ...

It is a very inattentive reader who fails to deduce that Mr. Wickham's seemingly courageous declarations have more to do with the absence of Mr. Darcy than any innate strength of character.

* * * * *

In the earlier chapters it has become clear that Mr. Collins intends to atone for the entailment so violently detested by Mrs. Bennet by marrying one or other of her daughters. In Chapter Fifteen he is shown changing his matrimonial intentions from Jane (as eldest – and prettiest) to Elizabeth (equally next to Jane in birth and beauty) on the hint of their mother as to Jane's imminent engagement to the wealthy and immensely eligible Mr. Bingley.

Mrs. Bennet treasured up the hint, and trusted that she might soon have two daughters married; and the man whom she could not bear to speak of the day before was now high in her good graces.

Except that Elizabeth is steadfast in her refusal to entertain even the thought of marriage to the tiresome Mr. Collins, and Mr. Bennet provokes his overwrought wife by supporting his favourite daughter in such a decision.

Which opens the door for Charlotte Lucas to hint strongly to the spurned suitor that any such proposal directed toward herself would be warmly welcomed. And Mr. Collins promptly and obligingly complies in Chapter 22.

Charlotte herself was tolerably composed ... Mr. Collins to be sure was neither sensible nor agreeable; his society was irksome, and his attachment to her must be imaginary. But still he would be her husband. Without thinking highly either of men or of matrimony, marriage had always been her object; it was the only honourable provision for well-educated young women of small fortune, and however uncertain of giving happiness, must be their pleasantest preservative from want.

Mr. Bennet pronounced himself gratified

... to discover that Charlotte Lucas, whom he had been used to think tolerably sensible, was as foolish as his wife, and more foolish than his daughter!

But humour is in short supply in these final pages of Volume I, and a reader is obliged to admit that even Miss Bingley's ascerbic but witty comments might be not entirely unwelcome.

* * * * *

I still intend to find that perfect English country house or manor to illustrate my Pride and Prejudice architectural analogy, but in these preliminary pages I thought I might make use of those buildings with which I am most unexpectedly familiar, which is to say buildings along the former St. James Street West in Old Montreal.

I've previously described [with accompanying photographs by Judy Turner, as part of my English! From Fairy Tale to Myth; Goldilocks to Doomsday Machine webpages], arriving as a just-turned-seventeen-year-old for my first day of work at 360 St. James on the south or sunny side of the street, and mentioned leaving without a backward glance for Place Ville Marie in 1966 when I would have just turned thirty.

The Provincial Bank Building between St. James Street where the original city Fortifications end at Saint-François-Xavier may not have been particularly beautiful apart from its lobby of fine imported dark green marble walls which some people admired, but my future husband and I worked in the same office in that building, wending our separate ways home in the evenings, until a certain Christmas party in uptown Place Ville Marie changed everything forever ...

But unlike PVM, there was nowhere to go at lunchtime in Old Montreal except out, to Woolworth's or the Honeydew, or to second-hand bookstores like Tally Ho! where I bought W.S. Gilbert's Bab Ballads as well as all his plays in four volumes. "You found those, did you?" said the proprietor with dismay. Those, and many other books besides, actually.

And further along Saint-François-Xavier to the south was — and still is — Montreal's English-language Centaur Theatre, housed in the former Stock Exchange. I go to six or so plays a year at the Centaur. Part of the pleasure of play-going is driving past and renewing acquaintance with all the old familiar buildings.

Yes, the old familiar buildings were designed and built as offices, for banks and insurance companies mainly, but hardly a month goes by nowadays without notice that yet another of these treasures has been purchased and is to be converted for use as a hotel or series of condominium suites. And plans for the Montreal buildings were usually based upon British or other European models, which in turn were invariably representative of classic Renaissance architecture.

And therefore perfectly suited to my self-indulgent research consisting of close examination of the relevant chapters of Sir Banister Fletcher's previously cited A History of Architecture, Sixteenth Edition. Of course I've been reading forever about the Enlightenment, and the Renaissance, but never before as if I were privileged to share in the excitement of it all, not merely the architectural, but literary and artistic as well, beginning with the invention of printing, and the consequent spread of knowledge engendering a spirit of inquiry and freedom of thought.

... Buildings came to be treated very much as pictures, largely independent of structural necessity, which had been the controlling element in Mediaeval times. Thus, by a reversal of the Mediaeval process, architecture became an art of free expression, with beauty of design as the predominant idea.

One of the most fascinating features of Sir Banister's book is his Comparative Analysis of various forms of architecture — for example between Gothic and Renaissance on Pages 601 to 606 where we are taught to look for

Skylines characterised

by horizontal cornices and balustrades, which give simplicity of

outline;

Door and window openings placed with regard

to symmetry and to grouping one above the other ... and spanned by

semicircular arches ... or lintels;

Columns ... appear either decoratively in façades

or structurally as in porticoes

Projecting horizontal cornices casting deep shadows ...

all combine to produce an effect of horizontality ...

Scottish Life Insurance

Building, Old Montreal

I wish I'd been told earlier about the shadows ...

In any event, with all that in mind, how could any mortal resist the picture of the building at the right, constructed in 1870 for the Scottish Life Insurance Company? This photograph appears in a website called Little St. James Street describing certain buildings located to the east of Place d'Armes. In addition to beautiful photographs, the website creator has provided archival research for these buildings and many others.

Note that there is no real division between the Foundation and Main Floor, but yet a strong horizontal line closes off that Ground Floor from the next level, preparing the eye for the dramatic projecting cornice at roofline. And far better too many floors than not enough.

The choice of Old Montreal's Scottish Life Insurance Building, of course, meant a rethinking of my original wish for columns — lots of columns, one for each character in the Novel. Which would have been simply wrong.

What's needed, obviously, is arches:— arches in groups, arcades. Matching or complementary arches for Mr. Darcy and Mr. Bingley; for Mr. Collins and Mr. Wickham; for the Bingley sisters Caroline and Louisa. And unlike columns, and their well-defined beginnings and endings, arches have an upward thrust which peaks and descends back downward to embed themselves in the actual framework, in a manner quite similar to the strong characters as written in Pride and Prejudice if not Jane Austen's other Novels.

My wish for columns was actually as a means to describe the phenomenon of female friendship, and in particular the lifelong closeness between Elizabeth Bennet and Charlotte Lucas. Time and again we see Elizabeth confiding in best friend Charlotte her reactions, her feelings, thoughts and intentions, particularly in regard to Mr. Darcy. We all know that an event cannot be said truly to have occurred until it's been thoroughly discussed with that one best friend.

Men's friendships are different in kind — the competitiveness or rivalry between Darcy and Bingley has no counterpart in authentic female friendships.

The Meryton Assembly, for example, and Darcy's sullen remark to Bingley:

"YOU are dancing with the only handsome girl in the room," said Mr. Darcy, looking at the eldest Miss Bennet.

Unthinkable in the context of a true feminine friendship, as proven by Charlotte's meticulous ascertaining that Elizabeth would die single rather than accept an offer from Mr. Collins before setting out to divert the latter's attentions to herself.

If exterior columns are completely unsatisfactory as a pictoral means of describing female friendships, perhaps interior piers might suffice. A recent newspaper announcement, this time of the the conversion to condos of the former London and Lancashire Life Insurance Building, came complete with a photo of the inside top of the gutted building. And what was to be seen but two iron piers projecting from the floor and embedding themselves into the roof. Narrow piers, sunk into the deepest foundations and ascending unremarked through ceiling and floor to the highest part of the roof — what better illustrative analogy for female best-friendships?

* * * * *

Pictures 3A

This Page Chapters 19 to 23, Ground Floor (6),

Finishing Touches Volume I

JMW TIurner, 1827

JMW TIurner, 1827

Title: Bookshelves and a Rococo Pier-Glass, with Several Figures, 1827

Medium: Gouache and watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 139 x 194 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22686

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

A Conversation Group

Medium: Gouache and Watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 190 x 140 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22743

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

Title: A Man Seated at a Table in the Old Library

Medium: Gouache and watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 141 x 191 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22691

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

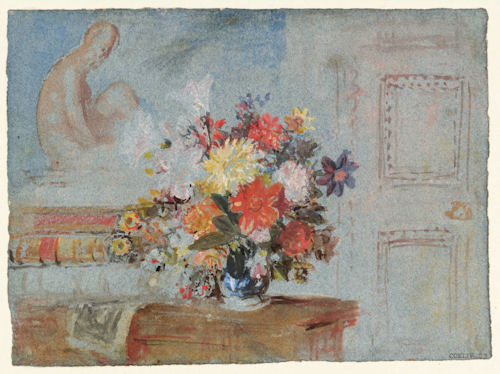

The Old Library: A Vase of Lilies, Dahlias and Other Flowers 1827

Medium: Watercolour and bodycolour on paper;

Support 139 x 188 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22685

The Scottish Life Building, Old Montreal

The Scottish Life Building, Old Montreal

Constructed 1870

Website: Little

St. James Street

www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape15/eng/15text5a.htm

________________________