With the attainment of Chapter Thirteen we have reached the Ground or Main level of Jane Austen's great mansion. Here, in these remaining pages of Volume I, Austen will begin to deal with the more public, less introspective aspects of her story, instantly serving notice that the plot has moved from careful preparation to headlong (comparatively speaking) action, as Mr. Bennet reads aloud a letter from his cousin Mr. Collins.

* * * * *

By Chapter Fifteen Mr. Bennet, his daughters (and with them the long-suffering reader) are only too well acquainted with the tiresome Mr. Collins, freeing Miss Austen to introduce a further complicating factor in the arrival in Meryton of the handsome and charming Mr. Wickham, about to become an officer in the militia.

Before continuing, perhaps I might be permitted to interrupt with a couple of comments?

Firstly, the unbearable goodness of Jane. In fact, what might have been insupportable is handled by Austen with such skill, delicacy and humour that we have the opportunity to work up no more than vague queasiness rather than the violent hatred usually aroused by true goodness of character.

Any competent writer can paint badness in all its shades and hues. (Actually, if any fault can be found with Pride and Prejudice, it lies in Austen's failure to show the slightest redeeming quality in the character of Mrs. Bennet, but this seeming failure may be perhaps the triumph of the novel — of which, more later.) Goodness, on the contrary, demands the utmost competence in literary portraiture. The most effective means seems to be the use of irony, a device which has the effect of making the character a source of ridicule, bringing him or her down to our level, where we can enjoy a good laugh at their expense. Jane does indeed come in for her fair share of sardonic authorial commentary, but in the main Austen chooses to show Jane's sterling qualities through the slightly exasperated affectionate teasing gaze of her clear-eyed younger sister.

It is, I believe, a simple two-word response interjected into Elizabeth's acerbic dialogue following the Meryton Assembly that enables Austen to keep Jane in the reader's grudging good graces:

WHEN Jane and Elizabeth were alone, the former, who had been cautious in her praise of Mr. Bingley before, expressed to her sister how very much she admired him ...

... 'Well, he certainly is very agreeable, and I give you leave to like him. You have liked many a stupider person.'

'Dear Lizzy!'

'Oh! you are a great deal too apt, you know, to like people in general. You never see a fault in any body. All the world are good and agreeable in your eyes. I never heard you speak ill of a human being in my life.'

'I would wish not to be hasty in censuring any one; but I always speak what I think.'

'I know you do; and it is that which makes the wonder. With your good sense, to be honestly blind to the follies and nonsense of others! Affectation of candour is common enough; — one meets it every where. But to be candid without ostentation or design — to take the good of every body's character and make it still better, and say nothing of the bad — belongs to you alone...'[Chapter Four.]

'Dear Lizzy!' Has there ever been a more economical delineation of love and acceptance than those two words? Jane's high standards apply to herself alone, with neither self-justification nor implied criticism of her plainspoken sister.

My second point has to do with the scarcity of eligible males in the immediate vicinity of the Bennet family circle. Charlotte Lucas, Elizabeth's close friend, is twenty-seven and has no apparent marriage prospects, not altogether surprising since her plain appearance is described several times by Mrs. Bennet to Mr. Bingley among others. But, until Mr. Bingley obligingly leases the nearby estate of Netherfield, even Jane, whose beauty is admitted by the overly critical Bingley sisters, is twenty-three years old and seems never to have had a suitor since a gentleman in London 'wrote some verses on her' when she was only fifteen, according to her mother.

Elizabeth, almost twenty-one, and Mary, two years younger, from the evidence are not able even to boast of inspiring poetry in a masculine admirer. In Elizabeth's case, this might be a good thing, since, as she informs a doubtful Mr. Darcy, 'I am convinced that one good sonnet will starve [love] entirely away.'

And yet the arrival of no fewer than four unrelated new young men upon the scene (to say nothing of an entire militia regiment!) is effected by Jane Austen with not the slightest appearance of contrivance. I wonder if part of the reason for our uncritical acceptance is her custom of using dual or paired entities: Bingley and Darcy; Mr. Collins and Mr. Wickham; even the two Bingley sisters Caroline and Louisa: always architectural harmony and balance.

In any event, it seems certain that the passage of years would bring an immense desperation to unmarried young ladies, as well as to their hopeful relatives. In the case of the Bennet family and the entailment to the nearest male relative 'who, when I am dead, may turn you all out of this house as soon as he pleases,' in the 'kindly' (?) words of their father [Chapter 13], the future is bleak indeed, with Mrs. Bennet and any unmarried daughters destined to live out their old age in the homes of such daughters as are successful in attracting a husband. Small wonder that the recent arrival in Meryton of the militia regiment would turn the heads of very young ladies such as Lydia and Kitty. Certainly their mother would do nothing to dampen the enthusiasm, if the passage from Chapter Seven previously cited is to be taken as a guide:

'I remember the time when I liked a red coat myself very well -- and indeed, so I do still at my heart; and if a smart young colonel, with five or six thousand a year, should want one of my girls, I shall not say nay to him; and I thought Colonel Forster looked very becoming the other night at Sir William's in his regimentals.'

As we will see, even Elizabeth is not immune to the charms of a handsome red-coated officer.

* * * * *

Pictures 3A

With the exception of the Hubble Footer, most Pictures on these

Pride and Prejudice, and other Austen webpages, are from the

Turner Bequest of the Tate Museum Collection Online.

This Page Chapters

13 to 23 inclusively: Ground Floor (1)

JMW Turner, 1818

JMW Turner, 1818

Title: Farnley Hall from the East

Medium: Bodycolour and chalk on paper

Dimensions: Support 311 x 394 mm

Private Collection, Turner Worldwide

Reference: TW0240, Wilton 587

JMW Turner, ?1798

JMW Turner, ?1798

A Gothic Arch in Mr. Wyndham's Garden at Salisbury, ?1798

Medium: Gouache, graphite and watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 477 x 329 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D02350

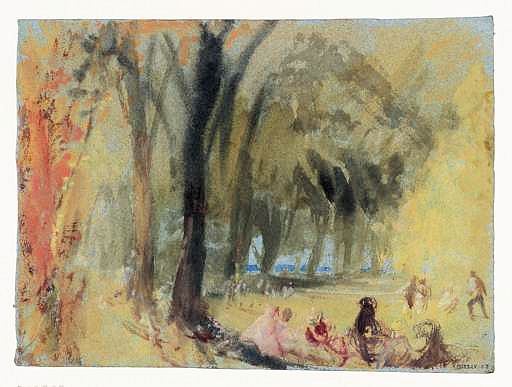

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

A Conversation Group

Medium: Gouache and Watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 190 x 140 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22743

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

A Fête Champêtre: East Cowes Castle 1827

Medium: Gouache on paper;

Dimensions: Support 142 x 191 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22722

________________________