________________________

A true child of the Empire, I was just turned seventeen, fresh out of High School, and woefully dependent still upon the Fairy Tales read to me by my beloved grandmother.

Did I forget to mention that at the top of the staircase facing the front door of my grandparents' house in Lachine was an enormous portrait of Queen Victoria accompanied by an equally huge tortoise shell? And that halfway down hung a horizontal frame containing oval side-by-side portraits of five English poets, or, rather, five poets who wrote in English counting Scott?

All this bolstered by ever-present schoolroom maps showing The World with Empire possessions and territories delineated in light red, I climbed onto a streetcar bound for Montreal and my first job, with a firm of Notaries in the Royal Bank Building on St. James Street West, at the corner of St. Peter, then the seeming apex of British Empire power and might, and what appeared to me a sensible and inevitable culmination of my journey through life as a loyal representative of English language and culture.

Then as now reality tries its best to interfere, beginning with street signs.

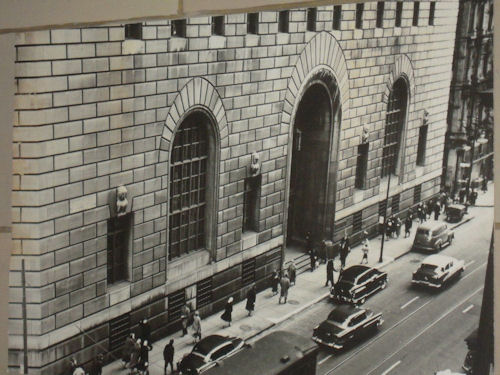

At left present day Notre-Dame Street entrance; to the right Saint-Jacques Street.

We had been warned that the eastbound streetcar would pass the Notre-Dame street rear entrance of the building, continuing to Notre-Dame Basilica where it would make a circle around Place d'Armes and return to Lachine in a westbound direction along St. James Street. Entering through the main door that first morning should help us get our bearings on leaving the building at night.

Except that something was wrong: the signs said rue Saint-Jacques and rue Saint-Pierre. Where, I asked plaintively, would I find St. James and St. Peter? Today I'd be told to try the Vatican, or to vas-t'en chez vous, or worse, but people then were less forthright. Little girl, you're standing on it, was the reply.

Eventually I learned to get off the streetcar on Notre-Dame Street and enter by way of the rear door of the building. And — what could be more British? — down the stairs and just to the left was a bookie's window, where I soon learned to place bets on the horses. That's a little joke on my part: in fact for a quarter I would be given a small piece of paper with prospective scores for that evening's hockey games. I won consistently, and was indignant when then Mayor Jean Drapeau, in an effort to stamp out crime, closed down the bookie. Drapeau lost the next election, the bookie was re-established; when he regained the mayoralty Drapeau forgot about crime and began planning to entice to Montreal the 1967 World's Fair.

________________________

Everything is just as when I worked there, including the letterbox shown at right, which I made liberal use of, with more enthusiasm than common sense. I suppose I would have identical emotions of dislocation and sadness if my grandparents' small house were still available to be viewed, rather than having been bought and demolished to make room for a particularly ugly duplex.

In those days the man who would become my husband also worked in the Royal Bank Building, although we had to wait for another time and another venue to meet and become acquainted. He wasn't posting silly letters but spent his time in the vault and safe deposit area taking care of valuables, which is where he caught sight of a flunkey returning a beautiful red enamel container, with gold trim, and followed it to the desk where he was permitted, after a sixty-day waiting period to verify that he was truly worthy, to rent the lovely object, safe deposit box #003, in exchange for his suddenly despised utilitarian black box.

He kept #003 rented, empty, for the next 45 years, and would have it still if it weren't for reality striking once again.

Judy was asked not to take photographs in the safe deposit area, so no picture is available.

________________________

Entrance to Royal Bank Branch

Entrance to Royal Bank Branch

All I remember about banking in this magnificent head office branch is taking the whole thing entirely for granted. And, worse, acquiescing whole-heartedly with my new employers' intention, some years later, of joining the herd leaving behind hidebound and old-fashioned St. James Street and Old Montreal, and moving uptown to Place Ville Marie, not coincidentally the head offices of the new Royal Bank Building.

Also not coincidence — Place Ville Marie, with its cruciform shape echoing the Cross on Mount Royal, was the work of an American dreamer/promoter named William Zeckendorf and a beginning of what was to become the famous Montreal Underground City.

Left behind was not only a British-inspired building but the influence of the British Empire; taking its place was meant to be a newly confident and bilingual Canadian nation, with a centre of gravity here in Montreal. Once again reality intervened; unexpected, unwanted, unnoticed until too late, American Hollywood triumphalism took the space vacated by British understatement.

American. But still gloriously, seductively, English.

Except that — ultimate irony — British English turned out to be far more inclusive of and friendly to the French language than American English will ever be.

________________________

________________________

#019 Royal Bank Building

#019 Royal Bank Building  #005 Letterbox

#005 Letterbox  #005 Letterbox

#005 Letterbox  #014 Another ceiling – wood

#014 Another ceiling – wood  #004 Ornate Ceiling

#004 Ornate Ceiling  #019 Royal Bank Building

#019 Royal Bank Building  #019 Royal Bank Building

#019 Royal Bank Building  #008 Safe Deposit area

#008 Safe Deposit area  #020 Address plaque

#020 Address plaque  #005 Letterbox

#005 Letterbox  #018 Photograph of old photo displayed at branch level

#018 Photograph of old photo displayed at branch level ________________________