Chapter Sixteen begins with Mr. Collins declaring the Philips home to be so admirable that he might almost have supposed himself in the small summer breakfast parlour at Rosings, and when his hostess

... had listened to the description of only one of Lady Catherine's drawing-rooms, and found that the chimney-piece alone had cost eight hundred pounds, she felt all the force of the compliment ...

The officers of the —shire were in general a very creditable, gentlemanlike set, and the best of them were of the present party; but Mr. Wickham was as far beyone them all in person, countenance, air, and walk, as they were superior to the broad-faced stuffy uncle Philips.

* * * * *

Since Mr. Wickham did not play at whist, he is free to spend the evening confiding in Elizabeth, herself only too ready to learn the meaning of the previous morning's strange encounter. Her curiosity is unexpectedly relieved. Mr. Wickham begins the subject himself, asking in an hestitating manner how long Mr. Darcy has been staying there, and whether he is likely to be in this country much longer. Elizabeth hopes that Mr. Wickham's plans will not be affected by Mr. Darcy's being in the neighbourhood.

'Oh! no — it is not for

me to be driven away by Mr. Darcy.

If he wishes to avoid seeing

me, he must go.

'A military life is not

what I was intended for,' continues Mr.

Wickham, 'but circumstances have now made

it eligible. The church ought to have been my

profession — I was brought up for the church, and I

should at this time have been in possession of a most

valuable living, had it pleased the gentleman we were

speaking of just now.' 'Indeed!' 'Yes —

the late Mr. Darcy bequeathed me the next presentation of the best

living in his gift. He was my godfather, and

excessively attached to me. I cannot do justice to

his kindness. He meant to provide for me amply, and

thought he had done it; but when the living fell, it

was given elsewhere.'

'Good heavens!' cried Elizabeth; 'but how could that be? — How could his will be disregarded? — Why did not you seek legal redress?'

'There was just such an informality in the terms of the bequest as to give me no hope from law. A man of honour could not have doubted the intention, but Mr. Darcy chose to doubt it — or to treat it as a merely conditional recommendation, and to assert that I had forfeited all claim to it by extravagance, imprudence, in short any thing or nothing. Certain it is, that the living became vacant two years ago, exactly as I was of an age to hold it, and that it was given to another man; and no less certain is it, that I cannot accuse myself of having really done any thing to deserve to lose it. I have a warm, unguarded temper, and I may perhaps have sometimes spoken my opinion of him, and to him, too freely. I can recall nothing worse. But the fact is, that we are very different sort of men, and that he hates me.'

'This is quite shocking! — He deserves to be publicly disgraced.'

'Some time or other he will be — but it shall not be by me. Till I can forget his father, I can never defy or expose him.'

Elizabeth honoured him for such feelings, and thought him handsomer than ever as he expressed them.

At this point Mr. Wickham explains that his father had been the late Mr. Darcy's steward (though never actually using the word), preferring to stress that although:

'...my father began life in the profession which your uncle, Mr. Philips, appears to do so much credit to — but he gave up every thing to be of use to the late Mr. Darcy, and devoted all his time to the care of the Pemberley property.'

After taking almost the entire Chapter Sixteen to recount in full Mr. Wickham's grievances toward Mr. Darcy, Miss Austen has Wickham overhear a chance remark by Mr. Collins concerning Lady Catherine de Bourgh, causing Wickham to volunteer to Elizabeth the fact that Lady Catherine happens to be Mr. Darcy's aunt, and that Mr. Darcy is expected to marry Lady Catherine's daughter, his cousin, thereby uniting the estates of Rosings and Pemberley.

On the website Amazon.com, buyers are encouraged to write reviews of their purchases. When I went to the Internet [in 2005] in search of information on the two BBC television miniseries available on videocassette, more than 600 persons had availed themselves of this privilege.

What do modern readers think of the fact that we seem unable to get enough of a novel written two centuries ago? What does Pride and Prejudice have that is lacking in current literature, and film? We are all entitled to our opinion. Mine is that readers today, and viewers, are given far too much information, affording no scope for imagination. Mystery is essential to us; why else do we dream? Or hope? Or pray?

Every age has its code words. Even in our overly mundane and materialistic time, certain matters — usually but not always of a sexual nature — find themselves alluded to rather than made concrete. I am thinking particularly of one of the 600 reviews mentioned above: I trust I am permitted to quote it?

'March 26, 2004. I don't read Jane Austen but the movie was good. Mrs. Bennet is trying to get her two oldest daughters Jane and Elizabeth married off. Jane is in love with Bingley, a newcomer to their town. Elizabeth is turned off by Mr. Darcy because he is aloof. She does fancy his half-brother [!] who is outgoing and courteous towards her. But things aren't what they seem above the surface.' The exclamation point is mine.

Are other readers as horrified as I was by this interpretation of Mr. Wickham's recitation? I went to the book immediately to reread Chapter Sixteen and scoff at the dirtiness of the minds of some people. There was no scoffing. In fact, my re-reading of the text was as if to the accompaniment of Don Basilio's aria La calunnia è un venticello (Calumny is a little breeze) in Rossini's The Barber of Seville: initial whispered doubt rising in volume through deepening suspicion to end in monstrous deafening certainty.

Of course the movie referred to above is the 1995 miniseries in which Mr. Wickham might be thought to resemble nothing so much as a larger coarser version of the film's Mr. Darcy, perhaps lending credence to an assumption so much at variance with Jane Austen's words. Viewers of the 1980 series would picture Mr. Wickham as I do, which is to say of a fair complexion and gentlemanly bearing in person, countenance, air, and walk in no way similar to Mr. Darcy. As far as we are concerned, what more natural outcome than that Mr. Darcy's father would be warmly disposed toward a golden-haired seemingly sunny-tempered steward's child, especially compared to his own son and heir, who gives every indication, as painted by Miss Austen, of having been born serious-minded and stately?

The following are the sorts of paragraphs come across in my rereading of the Novel Pride and Prejudice:

'His father, Miss Bennet, the late Mr. Darcy, was one of the best men that ever breathed, and the truest friend I ever had; and I can never be in company with this Mr. Darcy without being grieved to the soul by a thousand tender recollections. His behaviour to myself has been scandalous; but I verily believe I could forgive him any thing and every thing, rather than his disappointing the hopes and disgracing the memory of his father.' Elizabeth found the interest of the subject increase, and listened with all her heart; but the delicacy of it prevented farther inquiry ...

'... But what,' said she after a pause, 'can have been his motive? — what can have induced him to behave so cruelly?' 'A thorough, determined dislike of me — a dislike which I cannot but attribute in some measure to jealousy. Had the late Mr. Darcy liked me less, his son might have borne with me better; but his father's uncommon attachment to me, irritated him I believe very early in life. He had not a temper to bear the sort of competition in which we stood — the sort of preference which was often given me' ...

Elizabeth was again deep in thought, and after a time exclaimed, 'To treat in such a manner, the godson, the friend, the favourite of his father!' — She could have added, 'A young man too, like you, whose very countenance may vouch for your being amiable' — but she contented herself with 'And one, too, who had probably been his own companion from childhood, connected together, as I think you said, in the closest manner!'

'We were born in the same parish, within the same park, the greatest part of our youth was passed together; inmates of the same house, sharing the same amusements, objects of the same parental care ...'

'I had not thought Mr. Darcy so bad as this — though I have never liked him, I had not thought so very ill of him — I had supposed him to be despising his fellow-creatures in general, but did not suspect him of descending to such malicious revenge, such injustice, such inhumanity as this! ... His disposition must be dreadful.'

What, I wonder, did Miss Austen's genteel audience read into her story? She and they lived in an age when owners of large estates had seeming unlimited powers over employees, servants and tenants. A discreet dalliance with the wife of a steward, with or without her husband's complicity, certainly would not have been unknown. Readers of two centuries ago might have accepted Mr. Wickham's remarks as coded hints at an entitlement far beyond anything envisaged by today's more plain-spoken citizens, raising the possibility of the 1995 film being truer in this sense to the spirit of the original novel:

'He, Darcy, has so much: property, power, position, family ties, income. By rights I could demand a fair and just settlement. Yet even what little I ask is denied me.' Is this not the essence of Mr. Wickham's cleverly pathetic story?

On the other hand, attentive readers in the time of Jane Austen could not fail to grasp the mockery attending Elizabeth's naive and uncritical acceptance of the charming Mr. Wickham, his words and his exploits, quite unlike the more gentle irony extended toward her dealings with true gentlemen such as Mr. Darcy, Mr. Bingley, and Mr. Bennet. And plausible imposters of Mr. Wickham's sort were surely a staple of contemporary literature.

We will never know the truth. In any event, these conversational gambits between Wickham and Elizabeth during Chapter Sixteen's whist party take place in so gradual, so commonplace a fashion that the reader has no idea how tightly Mr. Wickham and Mr. Collins, together with the absent Mr. Darcy and his aunt Lady Catherine de Bourgh all are being woven by Miss Austen into the fabric of her story.

* * * * *

Just as Chapters Thirteen and Fourteen, arbitrarily assigned as first glimpses of Austen's Ground Floor, are ingenious reproductions at a higher level of Chapters One and Two as cornerstone of the entire eventual building, so Chapter Sixteen's Whist Party replicates the dramatic alteration in circumstance of my Foundation level Meryton Assembly.

If the Meryton Assembly showed Mr. Darcy as extremely unkind and unpleasant, Mr. Wickham's lengthy Whist Party recitations of his ill-treatment at the hands of the absent Mr. Darcy seem to bear out Elizabeth's involuntary exclamation: His disposition must be dreadful.

By way of transition, Chapter Seventeen is full of anticipation of the impending ball at Netherfield, and noteworthy for the fact that Elizabeth and her sisters Catherine and Lydia each mean to dance half the evening with Mr. Wickham. It hasn`t escaped our attention that as the events of the Meryton Assembly appeared to lead naturaly to the stay at Netherfield first of Jane and then of Elizabeth, so the Whist Party is to culminate in the Netherfield Ball.

And with Elizabeth, we await with anticipation the forthcoming meeting between the dreadful Mr. Darcy and the most gentlemanlike Mr. Wickham.

In architectural terms, I like to imagine Austen the builder methodically cementing columns and pillars in place before beginning work on the handsome staircase leading to the upper floors.

* * * * *

Pictures 3A

This Page Chapters 16 and 17: Ground Floor (4), The Whist Party

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

Title: Chatting with the Ladies

[separate detail Masthead and Left Column]

Medium: Gouache and Watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 141 x 189 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22747

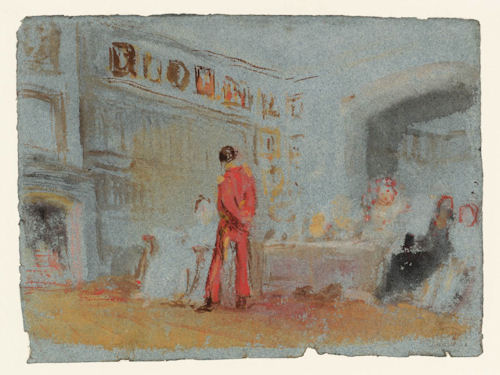

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

A Conversation Group

Medium: Gouache and Watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 190 x 140 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22743

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

The Red Uniform

Medium: Gouache and Watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 190 x 140 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D22684

________________________