We are meanderers in a hikers' world, rapt in contemplation of yesterday's moon and stars while our contemporaries stride purposefully toward tomorrow's sunrise.

Why we should love one bright particular star amongst the multitude of similar-seeming heavenly bodies spinning in the firmament is a mystery, but nothing will move us from our object of contemplation until we've extracted everything of meaning. And, perhaps, made it somehow our own by the mere act of investigation.

We can't unravel the mystery by staring into space; that would be too easy. We're forced to enter a darker, more forbidding universe: to look within ourselves, sifting through the sands of our unique knowledge and experience for random pieces of flotsam and jetsam that might help our search for meaning. How else are we to make sense of those powerful evocative reactions to certain books, films and television series — even to one special photograph of a group of eighty passed round a table — that seem to promise answers to questions that have tormented us lo, these many years? Since we were children, in fact, when asked why this Fairy Tale, and not that, would enchant us into contented slumber.

And sometimes it happens that significant numbers of others share not only our idiosyncratic compulsions, but also the conviction that the objects of our adoration are authentic Masterpieces, twinkling brightly each in its own distinct and private area of the night sky.

Why Masterpieces? Because the hallmark of every Masterpiece is uniqueness, so that it resists comparison with other objects of its type, in the same manner that Michaelangelo's David cannot be compared with other sculpture, nor Klimt's The Kiss with paintings of an identical subject matter.

Consider, for example, Jane Austen's sublime Pride and Prejudice, still read, televised, digitized, studied in university and generally existing as an industrial giant while other novels of the early 1800's arouse mostly perfunctory interest. So what if the rules stipulate that we're not at liberty to compare with objects of its type, which is to say, other novels? Not when we are permitted the use of illustrative analogy — a comparison of unlike things for the purpose of explanation *[Prose Models, Gerald Levin, 7th Edition, Page 457] — and compare Pride and Prejudice instead with architecture, and the design and construction of one of England's great mansions? And Seinfeld not with other television series, but rather a beloved comic strip?

Why not consider StarTrek as the distillation of every voyage of discovery, every manifestation of the human need to explore and explain and ultimately tame the unknown, and Blackpool as a visit to the Hall of Mirrors in a carnival, where we keep running up against distorted but immediately recognizable versions of ourselves? Meanwhile Dear Frankie might be best compared with — with what? Not any other film, perhaps, but with a certain unloved and unwelcomed sculpture, also now accounted a Masterpiece?

In the next section, I'll give definitions of common characteristics of my five chosen works, definitions which I use to harden my heart against friends who still insist I read those books, watch those films, or become addicted to those television series that I've rejected, as unproven, in advance.

And should that precious book, or film, or television series be as good as claimed, I'll catch up when it is merely timeless rather than current.

* See my webpage Acknowledgements for a proper appreciation of Gerald Levin's Prose Models, beginning with the convenient fact that I own copies of the First, Second, and Seventh Editions.

#001 The cause of it all :

#001 The cause of it all :  Detail

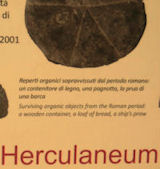

Detail [As of March 28th, 2013 the British Museum is holding an exhibition of artifacts from Pompeii and Herculaneum! How strange and unsettling to face directly the unearthed treasure hinted at obliquely in the photograph taken on May 8th, 2011 by Judy Oliver Turner of Herculaneum (modern Ercolano).]

________________________