Nailing down a specimen butterfly for clinical analysis is easy; it's no longer a butterfly, of course, merely a dead insect, but the thing could be done without encountering any of the problems inherent in defining something as peculiarly subjective as a Masterpiece.

But perhaps this present effort at definition is dangerous only to the credibility of its perpetrator, as Masterpieces have had to be extraordinarily hardy beasts, surviving initial disdain if not prolonged outright contempt. And of course the following definitions concern essential characteristics only of the five subjects chosen for this website, rather than of all Masterpieces.

In addition to the quality of uniqueness mentioned in the previous section, each of my five seeming random choices also shares the following essential characteristics that add the odd exuberant skip to the celestial sarabande of its orbit:—

Of course there's more.

It occurs to me that each and every selection in this present collection comes down ultimately to belonging and its opposite, exclusion. Perhaps all art is constructed about this basic concept.

It took place in Spring 2007, but I've never forgotten watching and listening as composer Philip Glass played an untitled piano composition on PBS, set to scenes of a new performing arts complex to be erected on the soon-to-be-demolished site of the Alice Tully concert hall at New York's Lincoln Center. It was an incredible piece of music, ancient and modern, simple and inordinately complicated, entirely composed of rapid-paced groupings of six-note chords. I'd never heard the work before, and yet it was strangely recognizable. At one point his hands wandered so far up the keyboard that it seemed impossible they would ever find their way back. But find his way back he did, at the only possible interval, as the piece became darker, more complicated, more familiar.

What do recognition and the feeling of belonging have in common that the emotions they arouse seem one and the same?

Is it possible that our hearts beat in a tempo very like the most perfect pieces of music? And send blood coursing through our veins and draw air into our lungs at a similar cadence? And that we are moved by music — and architecture, film and literature, indeed all successful artistic endeavours — to the extent that they resonate with our bodies as well as our minds? And this is why the scenes accompanying the music of Philip Glass were all about circulation, of people moving about the plaza, or driving vehicles through underground garages, culminating in a gloriously beautiful perfectly stylized group of buildings, the classical at the disposition of the utilitarian?

And if and when we finally achieve that elusive sense of belonging, is it not accompanied by a feeling of complete remembrance, of wholehearted recognition, even though we're never quite certain what exactly it is we are remembering?

Is not the crucial scene of Pride and Prejudice that moment in Chapter Forty-six when Elizabeth Bennet realizes that Mr. Darcy is just the man to suit her, to make her happy? That circumstances would appear to have removed him from her life forever in no way removes that moment of recognition under discussion. Seinfeld is all about Jerry's apartment as sanctuary for the chosen few (including Kramer whose presence is not precisely a matter of choice).

In Blackpool, there is no part of Ripley Holden's life that isn't envied by detective Carlisle, whose palpable driving force is the decision that if he can't have it, depriving Ripley of all he has, including liberty, is the next best thing.

For the characters populating the Scottish film Dear Frankie, the sudden and unexpected possibilities of belonging crowd out seemingly inevitable occasions for loss and humiliation.

As for Star Trek, it seems appropriate to bring up these points, to ask these questions in the context of a great work of science fiction, where the presence of unseen alternate realties can be taken for granted. If the presence of a parallel opposite universe can be made to seem plausible, and it can — see 'Mirror, Mirror', Star Trek Episode 33, Season 2-4 — why not a world in which we ourselves, mind and body, form a single entity with those artistic works which most touch the unexamined lives of human beings?

And is Star Trek's Mr. Spock so effective in conveying the reality of apartness, and exclusion, precisely because he is a Vulcan, bleeding green instead of red, biologically incapable of oneness with our universe? And yet we realize, with shock, that here we have been shown someone who has found, or been given, as second officer of The Enterprise, a place that lends him that fitful elusive precarious sense of belonging among humans, which he maintains only at unimaginable cost, to himself, and to those around him.

Certainly our reactions to books and films we hate: incomprehension, indignation, a feeling of rejection — are identical to those we experience when denied by the group, as is the triumph we know in rejecting an artistic offering as it has seemed to repudiate us. (Though sometimes our initial anger toward a film or book is accompanied by an inability to get the rejected work out of our minds, until somehow the film or book adapts itself to our bodily rhythms and mental structures and becomes utterly offhand and familiar, as happened with Dear Frankie, the final Retrospective of this series.)

________________________

The

Burghers of Calais Masthead

The

Burghers of Calais Masthead  Head

from a colossal bronze statue Left Column Top

Head

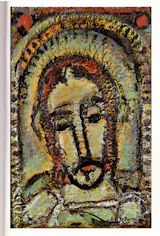

from a colossal bronze statue Left Column Top  Peter Denying Christ

Page Content

Peter Denying Christ

Page Content ________________________