I've mentioned in the previous webpage Part 2: Theme, Characters, Plot, under the heading Plot, that each paragraph of Jane Austen's Novel Northanger Abbey might be suited better to another webpage than Plot, to Deadly Sin, or to structure and Architecture, and in particular to Fairy Tale, with its transformative once upon a lifetime journey first to Bath and then to Northanger Abbey.

Of course this difficulty extends to the present webpage and Film, Fairy Tale/Myth, and Happily Ever After. I'm assuming that no one will be offended if I assign subjects in arbitrary fashion simply to the section where they can be tackled most easily:—

* * * * *

Cover Art, DVD

Northanger Abbey 2007

Whether it's a question of Deadly Sin, Theme, Characters, or suitability of Architecture and landscape, it's hard to imagine a more faithful filmed treatment of Jane Austen's Novel than the 2007 production of Northanger Abbey shown on North American PBS channels — faithful were it not for the fact that the film makers have chosen to simplify greatly the Plot of an already clear, straightforward and simple Novel, thereby depriving the viewer of any hint of Fairy Tale while they were about it.

Of all Jane Austen's Novels, it is Northanger Abbey which most makes use of a Cinderella plot pure and simple, with handsome Prince Charming encountered at the Ball, and his necessary quest to find the lovely lost princess in her home among the cinders and free her from undeserved solitude and deprivation. The whole aided by an unlikely Fairy Godmother who comes in unexpectedly at the end of the story to wave her magic wand and dispatch Cinderella to her inevitable destination at the side of the Prince. Of course each Fairy Tale contains its own distinct detail, and in the case of Northanger Abbey the transformative once upon a lifetime journey begins in Bath with vividly portrayed humans standing in for loathsome avaricious ogres and fire-breathing dragon, before moving on to Northanger Abbey for the final confrontation which is no less shattering for being unmistakeably if elliptically foreshadowed and predicted.

To quote from my introductory webpage dealing specifically with Fairy Tale and Myth:—

Every Fairy Tale is a journey, a bewildering travel from a time before time to a completion beyond the constricting limits of childhood, and aloneness, to a culmination point of all living happily ever after.

Gustave Dore, Reading Fairy Tales

illustration in my website

Fairy Tale and Myth

And yet it is precisely that essential Fairy Tale journey which has been — no, not omitted but, worse, disparaged in the 2007 film, as though in the last pages of her Novel Jane Austen had told a joke, and the film faithfully delivered the setup, but failed to follow through with the punchline.

Yes, Catherine's mother Mrs. Morland is indeed shown, in Novel as in film, to be of the opinion that Catherine's journey has been an unimportant interlude and that her eldest daughter has now the obligation to forget all that nonsense and resume her familial duties at Fullerton as though nothing has happened.

But the film has ignored the essential ingredient of the glass slipper, which is to say the Novel's portrayal of a Henry Tilney who has a job, a purpose, a private income, a sister in need of a trusted friend, a home in the parsonage at Woodston nearly twenty miles from Northanger Abbey, and who has gone to the ball at Bath in search of that one happy and loving and beautiful princess whose foot will fit into all aspects of his Prince Charming life, personal and professional.

The 2007 Film finds more interest in christenings than fairy tale princesses and glass slippers, starting and ending outside the Fullerton church with the baptism of baby Catherine in the first instance, and Catherine as mother in the last, thus continuing the Morland tradition of amorphous large families of undifferentiated children.

And what of the Henry Tilney shown in the 2007 Film of Northanger Abbey with his announcement that he will probably be disinherited by his father him leaving him destitute, and, oh yes, will you marry me, Catherine? other than as the hero of a particularly nasty anti-fairy tale, as though Prince Charming has come to stay with Cinderella in the cinders of the chimney of the Morland house in Fullerton. And Catherine is shown dutifully accepting the role which has been chosen for her as penance for her sins of unbecoming assumption and unworthy aspiration, a role of Mother of wilfully impoverished Henry as well as the younger Morlands and a vast horde of Tilneys born and as yet unborn.

Today's young people seem to delight in horrifying themselves with zombies and vampires; but there was no delight whatsoever in my childhood encounter with Ibsen's Button-Moulder, who frightens me to this day with his introductory words to Peer Gynt:—

"I have been sent for you ... you are to go into my ladle ... I must melt you up ..." [in the ladle into which all must go to be melted who are ...] "not bad enough for the sulphur pit, nor good enough for Paradise."

Peer Gynt protests, on his own behalf, and ours, that he cannot be turned into a button like all the others:—

"You cannot kill a soul! Haven't I been a personality? An individual? Myself?"

And the play ends, dreadfully, at least for a child, with the Button-Moulder's implacable voice:—

"We shall meet again, Peer Gynt. And then we shall see ..."

Citations from TheatreHistory.com: PEER GYNT: A synopsis of the play by Henrik Ibsen

And here we have a film ending with the unfortunate Catherine Morland already pressed into button-mould mother of untold children, when she hasn't even yet been a differentiated soul. A personality. An individual. Herself.

Another quibble, this time concerning a less consequential matter, which is to say the invented scene where Isabella falls from an already uneasy grace with Captain Frederick Tilney, and might have culminated in better dialogue on the part of Isabella — perhaps something more in keeping with that young lady's arrogance and stupidity such as "Won't my sisters be envious when they learn that I am engaged to Captain Frederick Tilney!" — with the captain's vicious response as before.

Except upon reflection I realise the existing words, inane as they are, serve to assure the viewer that the scene we are watching does not form part of Jane Austen's witty Novel. I confess with shame to having gone back to that Novel in search of proof of the film's allegation by Henry that his father the General was interested in marrying Catherine himself. There is no such proof, of course, since Austen has explicitly twice stated the opposite in the second-to-last paragraph of the second-to-last chapter:—

' ... From some hints which had accompanied an almost positive command to his son of doing everything in his power to attach her ...

' Henry's indignation on hearing how Catherine had been treated, on comprehending his father's views, and being ordered to acquiesce in them, had been open and bold. The general, accustomed on every ordinary occasion to give the law in his family, prepared for no reluctance but of feeling, no opposing desire that should dare to clothe itself in words, could ill brook the opposition of his son ... But, in such a cause, his anger, though it must shock, could not intimidate Henry ... and believing that heart to be his own which he had been directed to gain, no unworthy retraction of a tacit consent, no reversing decree of unjustifiable anger, could shake his fidelity, or influence the resolutions it prompted. '

Northanger Abbey, citations from Volume II, Chapter 15 [ch. 30 of 31]

I suppose if film makers have ignored existing fairy tale elements in the Novel they are adapting, they are forced to invent others whether justified or not.

At least the 2007 film follows the Novel in showing the undoubted close affection between brother and sister Henry and Eleanor Tilney, reminding us that for people living under tyranny — and General Tilney is a particularly demanding and rigid domestic tyrant — our only recourse lies in the ability to control how we treat those around us. Not a seemingly radical course of action, but one considered sufficiently dangerous to earn Czech writer and dissident Vaclav Havel who proclaimed it in 1977 a stay in prison prolonged until the fall of the actual existing political regime — when he was carried by supporters from prison literally up to the fairy tale castle at the top of the hill in Prague.

Now there's a true fairy tale ending.

* * * * *

Cover Art, DVD

The Merchant of Venice 2004

UK region 2

Act I, Scene I

ANTONIO. In sooth, I know not why I am so sad.

It wearies me; you say it wearies you;

But how I caught it, found it, or came by it,

What stuff 'tis made of, whereof it is born,

I am to learn;

And such a want-wit sadness makes of me

That I have much ado to know myself.

Citation from

The Merchant of Venice, William Shakespeare, 1597 gutenberg.org

I am to learn. As a rule the metre in these short lines is taken up and completed in those following. Not so the four simple words which are left to stand alone and thereby acquire even greater meaning. It's hard to imagine any medical journal in the intervening four hundred years containing a more devastating description by a patient of the curse of depression and bewildered admission of need for a cure than we hear in this speech of Antonio, The Merchant of Venice, which opens Shakespeare's stage play of the same name.

If my belief that each of Jane Austen's Novels is an illustration of one of the Seven Deadly Sins can be accepted, and further that Avarice is the Sin in question in Northanger Abbey, then we have to ask ourselves what Jane Austen was about in inserting what seems an unnecessarily gratuitous, insistent and repeated declaration by John Thorpe that Catherine's kind host Mr. Allen is as rich as a Jew. Perhaps she means simply to imply that only a person as witless and opinionated as Thorpe would use such an expression, but she must have known that in any study of Avarice, the words rich and Jew together would elicit comparisons with Shakespeare's moneylender Shylock.

No one in the world is as unintentionally judgmental as a reader, theatre-goer or film viewer. As soon as we have been made aware of an inappropriate transgression of society's rules, we are ready to demand artistic retribution, the severity of which is determined not by the seriousness of the transgression but by the sincerity of time-honoured confession and acceptance of penance. The transgressions to be punished in The Merchant of Venice are usually considered to be Shylock's inappropriate avarice as a usurer or money lender, and Antonio's unsuitable fondness for his kinsman Bassanio.

If our opinion of Shylock is overshadowed by the danger of overt antisemitism, that of Antonio is clouded by reflexive contempt for an elderly gay man putting his entire fortune — not to say his life — into the hands of a money lender for the sake of unrequited love for a beautiful young man.

And then there is the shocking 2004 film of The Merchant of Venice — shocking because nothing causes us as much inner upheaval as the need to change a deeply held opinion — Antonio is not gay in either modern sense of the word, but rather clinically depressed, and his sad face breaking into a smile as he beholds Bassanio is perfectly understandable when we reflect upon the pleasure we take in the mischievous antics of our beloved nephews and nieces and grandchildren, pleasure neither depraved nor unsuitable, but simple acknowledgement that these young people cheer us up, lifting us from the immutable muck of our everyday lives to a carefree atmosphere where everything is possible and all is forgiven.

And if that not be shock enough to our overburdened senses, we get to see and hear a Shylock whose besetting sin is not Avarice — how can someone be avaricious who refuses to accept any monetary return on his loan of three thousand ducats even when offered an unimaginably large amount — "Pay him double six thousand, and then treble that," says Portia in Act III, Scene II — but, rather, Pride. And who would dare to say that Shylock's injured Pride is unjustified, inappropriate, when Antonio, the person coming to him for a loan, has not only spat upon him but

SHYLOCK, Act III, Scene I

... disgrac'd me and hind'red me half a

million; laugh'd at my losses, mock'd at my gains, scorned my

nation, thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine

enemies. And what's his reason? I am a Jew ...

...

If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility?

Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his

sufferance

be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach

me

I will execute; and it shall go hard but I will better the

instruction.

And so perhaps it might be agreed that while Shylock's contemplated revenge be inappropriate, his pride is not, and further that The Merchant of Venice is the study of Avarice's opposite, as any element or factor can be understood fully only by examination of what it is not.

I've given my opinion that generosity is the opposite of Avarice (and Pride, and Envy, and undoubtedly all the other Deadly Sins besides), and is it not possible that the words inserted by Austen into the mouth of the insufferable John Thorpe are an act of generosity on her part meant to bring to the attention of her readers without actually saying so that with the advent upon the London stage of actor Edmund Kean (1787-1833), Shakespeare's Shylock has ceased to be the consummate villain of Drury Lane? According to Wikipedia:—

' Jewish actor Jacob Adler and others report that the tradition of playing Shylock sympathetically began in the first half of the 19th century with Edmund Kean,[8] and that previously the role had been played "by a comedian as a repulsive clown or, alternatively, as a monster of unrelieved evil." Kean's Shylock established his reputation as an actor.[9] '

Citation from Wikipedia, The Merchant of Venice

Edmund Kean appears to have been the foremost Shakespearean actor during Jane Austen's lifetime. Once more according to Wikipedia:—

' His opening at Drury Lane on 26 January 1814 as Shylock roused the audience to almost uncontrollable enthusiasm ... " '

Citation from Wikipedia, Edmund Kean

And to continue with Wikipedia, its entry for Northanger Abbey states that the Novel was the first of Jane Austen's Novels to be completed for publication:—

...

' The novel was further revised by Austen in 1816/17, with the

intention of having it published ... '

Citation from Wikipedia, Northanger Abbey

To remember that Austen died in 1817 aged 41 and some months, while imagining what would be required in order to make the simplest revisions using quill pen and ink to an existing handwritten manuscript, is to be grateful for what we have been left of her works including this Novel.

* * * * *

In the Nathaniel Hawthorne version of the Midas myth, Midas's daughter turns to a statue when he touches her. Illustration by Walter Crane for the 1893 edition.

Citation and Picture from Wikipedia, Midas

Journeys and Arrivals

I've stated on many occasions throughout this website my belief that

Fairy Tale is an artistic and spiritual rendering into the simplest

possible terms of the shattering upheavals experienced by a small human

fledgling leaving its comfortable nest on the necessary Fairy Tale journey

to adolescence, where it arrives at the ultimate destination with everything

altered in its circumstances, but itself essentially unchanged.

And Myth is the story of that arrival, only to find that instead of having earned tranquillity after the upheaval of its travels, the young person has now to deal with its own now bewildering changes, outwardly and inwardly, as it leaves behind childhood and safety and assumes the fearful trappings of adolescence.

At first glance it appears that the ancient Greek tale of King Midas is the perfect Myth to illustrate the Deadly Sin of Avarice, and so it is. But I believe that a large part of its impact, particularly as told by Nathaniel Hawthorne in the only version I have ever read until now, is that the story meshes so perfectly with the fears of adolescence, those atavistic fears that changes in oneself are unstoppable, uncontrollable, and will get out of hand.

And who better to hold responsible than one's father, who should know better, should know how to protect us rather than leading us into further harm? And even more so when it is explicitly stated in the Myth that it is his daughter, his child, the only thing that Midas really loves, who is killed by his agency, being turned into a golden statue when he touches her.

I'd just like to conclude by mentioning that I'm not aware of any other Deadly Sin sharing with Avarice a single illustrative feature, seen in every story of Avarice from the Latin Play Aulularia by early Roman playwright Titus Maccius Plautus, to Molière's 1668 L'Avare, to Dickens's A Christmas Carol's Ebenezer Scrooge, (and Disney's Scrooge McDuck):— that of a barred and booby trapped strong room containing a solitary male figure engaged in counting his riches (and in the case of McDuck throwing gold and silver coins in the air to fall about himself with joyful abandon. And leaving to the regretful adult who once dreamed of such earthly fulfilment a realisation that the procedure so hoped for would be undoubtedly extremely painful even for a human let alone an elderly creature of the canardly persuasion.)

* * * * *

' Mr. and Mrs. Morland's surprise on being applied to by Mr. Tilney for

their consent to his marrying their daughter was, for a few minutes,

considerable ... and, as far as they alone were concerned, had not

a single objection to start.

' There was but one obstacle, in short, to be mentioned;

but till that one was removed, it must be impossible for them to sanction

the engagement. Their tempers were mild, but their principles were steady,

and while his parent so expressly forbade the connection, they could not

allow themselves to encourage it ... His consent was all that they wished for.

...

' ... What probable

circumstance could work upon a temper like the general's? The

circumstance which chiefly availed was the marriage of his daughter with

a man of fortune and consequence, which took place in the course of the

summer — an accession of dignity that threw him into a fit of good humour,

from which he did not recover till after Eleanor had obtained his

forgiveness of Henry, and his permission for him "to be a fool if he

liked it!"

' The marriage of Eleanor Tilney ...

' [Eleanor's] partiality for this gentleman was not of recent

origin; and he had been long withheld only by inferiority of situation

from addressing her. His unexpected accession to title and fortune had

removed all his difficulties; and never had the general loved his

daughter so well in all her hours of companionship, utility, and patient

endurance as when he first hailed her "Your Ladyship!"

...

' ... Henry and Catherine were married, the bells rang, and

everybody smiled; and, as this took place within a twelvemonth from the

first day of their meeting, it will not appear, after all the dreadful

delays occasioned by the general's cruelty, that they were essentially

hurt by it. '

Northanger Abbey, Volume III, Chapter 31 [ch. 31 of 31]

Austen herself apologises at the end of the Novel for not introducing earlier, or at all, Eleanor's temporarily ineligible suitor, who turns out to be a highly important mover of the action. But the presence of the young man in question is not necessary for understanding either the Theme of discernment of the genuine, nor the Deadly Sin of Avarice, both of which subjects are adequately dealt with in the Novel.

And it appears to me that we are better off without the young man, estimable though he may be, since it forces us to understand how difficult it is for lives in the time of Jane Austen to end Happily Ever After. And to understand also what consolations it would bring, to young people and their parents alike, to read Novels ... dependable Novels like Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey, for example which do indeed, and against all odds, end Happily Ever After.

In the next section, an examination of Northanger Abbey as it relates to Architecture and Absences, is meant to be a seamless continuation of this present study.

* * * * *

Details of and links to all Austen-Novel Pictures are found either in the Pictures 3B or the present Pictures 3B Group II webpages.

This Page:—

Northanger Abbey Part Three: Film, Fairy Tale, Myth and Happily Ever After

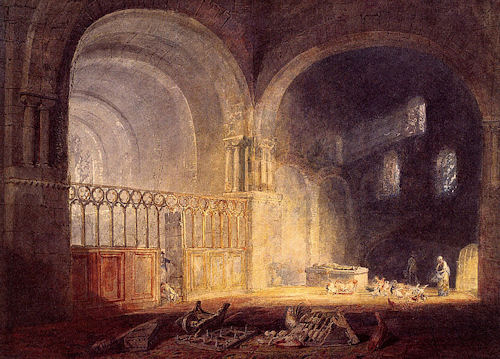

JMW Turner, exhibited 1798

JMW Turner, exhibited 1798

Title: Refectory of Kirkstall Abbey, Yorkshire

Medium: Graphite and watercolour on paper

Dimensions: Support 448 x 651 mm

Collection: The Trustees of Sir John Soane's Museum

Turner Worldwide, Reference TW 0528, Wilton 234

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

Title: At Petworth: Morning Light through the Windows

Medium: Gouache and watercolour on paper

Dimensions: support: 140 x 191 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference: D22774 Turner Bequest CCXLIV 112

JMW Turner, 1797

JMW Turner, 1797

Kirkstall Abbey South Aisle and Nave from the South Transept

Medium: Graphite on paper

Dimensions: Support 368 x 262 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

View this artwork in the Tweed and Lakes Sketchbook

Reference D01083

Turner Bequest XXXV 81

JMW Turner, circa 1797

JMW Turner, circa 1797

Title: Transept of Ewenny Priory, Glamorganshire

Medium: Watercolour over pencil on paper

Dimensions: 40.1 x 55.7 cm

Collection Amgueddfa Cymru — National Museum Wales (Cardiff, UK)

Turner Worldwide

Reference: NMW A 1734

Cover Art, DVD

Cover Art, DVD

Amazon.com Northanger Abbey 2007 Masterpiece Theatre

also

Wikipedia, Film Northanger Abbey 2007

Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Complete Fairy Tales by Charles Perrault, with a new

translation by Christopher Betts, Oxford University Press

<— At left Reading the tales to the family, Frontispiece

—>

At right Front cover of dust jacket, also Page 102, Red Riding Hood

is surprised to see what her Grandmother looks like

[from my website

Fairy Tale and Myth — Pictures-2]

![Thumbnail, Cover art, DVD <em>The Merchant of Venice</em> 2004 film [UK Region 2]](../dvd-the-merchant-of-venice-thumbnail.jpg) Cover Art, DVD

Cover Art, DVD

Amazon.co.uk The Mrchant of Venice 2004 UK Region 2

— also —

Wikipedia, Film The Merchant of Venice 2004

— also —

Wikipedia The Merchant of Venice, William Shakespeare, believed to have been written

between 1596 and 1598

In the Nathaniel Hawthorne version of the Midas myth,

Midas's daughter turns to a statue when he touches her.

Illustration by Walter Crane for the 1893 edition.

Citation and Picture from Wikipedia, Midas

________________________