In writing these webpages describing Jane Austen's Novel Northanger Abbey, I have moved to Architecture, or structure, anything relating to what might be called the various levels of narration, which is to say, in no particular order, the divisions between Catherine Morland as voracious reader of Gothic Novels, actual Catherine as heroine/narrator, and failed Catherine as representative of Gothic Novel heroines.

One noteworthy peculiarity of Northanger Abbey is an Advertisement or foreword by Jane Austen written in 1816 a year before her death, explaining that the book had been finished thirteen years previously, in 1803, and begun even earlier, and that during that period, places, manners, books and opinions have undergone considerable changes.

Except that she needn't have apologised since her Novel is a witty parody of Gothic horror novels which are proving to be as difficult to kill off once and for all as the vampires so often contained in their pages. And it appears to me that if Jane Austen wished to apologise for any of her Novels she might have done better with an Advertisement or foreword to Sense and Sensibility calling upon the reader to refrain from expecting any sense at all, precious little sensibility, but lots and lots of envy and spiteful disparagement.

* * * * *

It seems obvious that a Novel dealing with the need to discern the artificial from the genuine would necessarily exist on different levels, but less obvious that the levels would include a heroine/narrator who is addicted to Gothic horror novels, and in particular a specimen entitled The Mysteries of Udolpho, A Romance Interspersed With Some Pieces of Poetry, into which our intrepid Miss Catherine Morland buries her head at every possible moment, to the detriment of mundane reality about her.

Fate sits on these dark battlements, and frowns,

And, as the portals open to receive me,

Her voice, in sullen echoes through the courts,

Tells of a nameless deed.

From the title page of a Transcript of The Mysteries of Udolpho, Ann Radcliffe, published 8 May 1794 found at Gutenberg.org

When Northanger Abbey was first begun during the middle of 1798 ... and completed about a year later (Wikipedia), the youthful Jane Austen undoubtedly assumed that Mrs. Radcliffe's Udolpho Novel then fashionable would be still relevant in the minds of her readers no matter how much time elapsed, and the fact that this was the first of her Novels to be accepted for publication in early 1803 would appear to buttress that opinion. And Austen cannot be blamed for the fact that when she repurchased copyright to that inexplicably unpublished book in 1816 shortly after the publication of 'Emma', it was faced with launching onto a vastly altered literary landscape.

I still maintain that her reason for not simply forgetting about Northanger Abbey and moving on to the next manuscript is that Jane Austen's intention was always to write a separate Novel for each of the Seven Deadly Sins, and Northanger Abbey, including its Gothic horror novel overlay, is at heart an extremely efficient treatment of Avarice. — An extremely simple Novel describing an extremely simple and uncomplicated human failing. To our modern sensibilities it might — does — appear that there are far more serious transgressions worthy of examination, but Jane Austen was seemingly content to limit herself to that traditional list of seven.

According to Catholic moral thought, the seven deadly sins are not discrete from other sins, but are instead the origin ("capital" comes from the Latin caput, head) of the others. Vices can be either venial or mortal, depending on the situation, but "are called 'capital' because they engender other sins, other vices".[2]

And strange as it may seem, the Gothic Novel elements are not used to move the Novel forward, as a modern writer would insert a murder, and detective to solve it, but rather to mimic the pretentious demeanour of the avaricious triad of Isabella and John Thorpe and General Tilney. And by what is surely not coincidence, these elements also reinforce the Theme of discernment of the genuine as opposed to the artificiality of these strong-minded antagonists who are determined to have their way against the very young and seemingly pliable and weak-willed Catherine.

Isabella became only more and more urgent ... She was sure her dearest, sweetest Catherine would not seriously refuse such a trifling request to a friend who loved her so dearly. She knew her beloved Catherine to have so feeling a heart, so sweet a temper, to be so easily persuaded by those she loved.

Even though the opening chapter of Northanger Abbey seems to set up Miss Radcliffe's Novel as being the summit to be striven for, and to find our heroine sadly lacking in the necessary fictional attributes for such an exalted journey, we soon perceive that Catherine Morland's ordinariness and lack of ostentation bestow a decided protection against the pressures to conform to society's unwritten rules with which she does not agree.

Catherine felt herself to be in the right,

and though pained by such tender, such flattering supplication, could not allow

it to influence her.

Isabella then tried another method ...

"I cannot help being jealous, Catherine, when I

see myself slighted for strangers, I, who love you so excessively! When once

my affections are placed, it is not in the power of anything to change them.

But I believe my feelings are stronger than anybody's; I am sure they are too

strong for my own peace; and to see myself supplanted in your friendship

by strangers does cut me to the quick, I own."

Northanger Abbey, citations from Volume I, Chapter Thirteen

Another function of the Gothic horror novel overlay is to draw attention from factors which would be remarkable but have nothing to do with Avarice or the Theme of discerning the genuine, factors like the breath-taking self-absorption of Mrs. Allen and, even more to the point, like the extreme cruelty of Captain Frederick Tilney's annual hunt for the prettiest girl enjoying a season in Bath, to be seduced away from worthier and more eligible suitors and abandoned for other quarry when her attractions have become too well-known.

There is one additional benefit from the Gothic horror novel elements, and that is to temper somewhat with their silly extravagances the bleakness of what I describe in the previous chapter as the Happily Ever After conclusion to Northanger Abbey's Fairy Tale journey.

In Pride and Prejudice, the happy ending is entirely within the control of its hero Mr. Darcy (and heroine Elizabeth Bennet, of course), and although we never forget the extreme vulnerability of the Bennet family, still we are able to enjoy an unclouded pleasure in the ending of Novel, film, or miniseries adaptation. But the overwhelming sensation of heading toward an inexorable and inescapable conclusion that makes the reading of Pride and Prejudice such an enjoyable experience, is entirely lacking in her next two Novels.

Sense and Sensibility's hapless hero Edward Ferrars is very much under the control of his hateful mother Mrs. Ferrars; who (1) wishes him to add to the family wealth and position by an arranged marriage with a titled heiress; and (2) has no qualms about withholding the inheritance to which he is entitled should he dare to refuse to comply with her ambitious plans. The 1995 film might have a very satisfying conclusion, mainly because it shifts focus from envy to generosity, but such a transformation is impossible to the Novel which has in view always a different and very serious objective.

Unlike the hapless Edward, Northanger Abbey's Henry Tilney has a very considerable fortune secured by marriage settlements, and, as well, his present income was an income of independence and comfort. And Catherine Morland's parents are all that is affectionate and reasonable, as is their insistence that there can be no marriage between their daughter and Henry Tilney without his father's approval. And here we begin to understand why every lasting and powerful artistic representation of Avarice begins with that solitary male figure locked inside a barred room while he counts up his treasure. Because the miser's entire life's work has consisted in the accumulation of sufficient power and riches to enable the moment where he can — will — tyrannise his family (as well as the outside world) by forcing everyone to accede, helplessly, against his or her wishes, to the pecuniary imperatives of Avarice.

' The general, accustomed on every ordinary occasion to give the law in his family, prepared for no reluctance but of feeling, no opposing desire that should dare to clothe itself in words ...'

Northanger Abbey, Volume II Chapter Fifteen [ch 30 of 31]

'No reluctance but of feeling, no opposing desire that should dare to clothe itself in words.' A perfect description of the domestic tyrant. What exultation in seeing on the faces of his children that reluctance which dares not express itself in words. It is only with the greatest difficulty that a reader can imagine the pain and anguish inspired in the sensitive and compassionate Eleanor to be obliged to inform invited guest Catherine that the general has ordered her departure the following morning, with no maid to accompany her. And the ever obedient ...

' Eleanor seemed now impelled into resolution and speech.

"You must write to me, Catherine,"

she cried; "you must let me hear from you as soon as possible. Till

I know you to be safe at home, I shall not have an hour's comfort. For one

letter, at all risks, all hazards, I must entreat. Let me have the satisfaction

of knowing that you are safe at Fullerton, and ... I will not expect more. Direct

to me at Lord Longtown's, and, I must ask it, under cover to Alice."

"No, Eleanor, if you are not allowed to receive

a letter from me, I am sure I had better not write. There can be no doubt

of my getting home safe."

Eleanor only replied, "I cannot wonder at your

feelings. I will not importune you ..." But this, with the look of sorrow

accompanying it, was enough to melt Catherine's pride in a moment, and she instantly

said, "Oh, Eleanor, I will write to you indeed."

There was yet another point which Miss Tilney was anxious

to settle, though somewhat embarrassed in speaking of. It had occurred to her

that after so long an absence from home, Catherine might not be provided with

money enough for the expenses of her journey, and, upon suggesting it to her

with most affectionate offers of accommodation, it proved to be exactly the case.

Catherine had never thought on the subject till that moment, but, upon examining

her purse, was convinced that but for this kindness of her friend, she might have

been turned from the house without even the means of getting home; and the distress

in which she must have been thereby involved filling the minds of both, scarcely

another word was said by either during the time of their remaining together. '

Northanger Abbey, Volume II Chapter Thirteen [ch 28 of 31]

"For one letter, at all risks, all hazards, I must entreat." Obviously Eleanor assumes that she too will be treated with all the considerable cruelty of which the general is capable should her unaccustomed defiance be discovered, and we are entitled to assume that the possibility of such an unlikely event has never entered her father's mind. But a dutiful daughter offers poor sport, and the general must have awaited with increased anticipation the return to Northanger of his second son Henry.

' [Henry]'s indignation on hearing how Catherine had been

treated, on comprehending his father's views, and being ordered to acquiesce

in them, had been open and bold ...

[He] steadily declared his intention of offering her

his hand. The general was furious in his anger, and they parted in dreadful

disagreement. '

citations from Volume II Chapter Fifteen [ch 30 of 31]

General Tilney happens to be extremely rich and powerful, but it takes little effort to understand that in Jane Austen's time every parent had the capacity to forbid what was considered an unsuitable marriage, and, even worse, to extort an unwelcome union from sons as well as daughters.

But Jane Austen needs a happy ending for her Novel, and therefore inquires of her readers in the final Chapter 31:—

' What probable circumstance could work upon a temper like the general's? The circumstance which chiefly availed was the marriage of his daughter with a man of fortune and consequence, which took place in the course of the summer — an accession of dignity that threw him into a fit of good humour, from which he did not recover till after Eleanor had obtained his forgiveness of Henry, and his permission for him "to be a fool if he liked it!" '

citations from Volume II Chapter Sixteen [ch 31 of 31]

We note that Eleanor's partiality for this gentleman, which is to say for the man of fortune and consequence whom she marries so conveniently,

' ... was not of recent origin; and he had been long withheld only by inferiority of situation from addressing her. His unexpected accession to title and fortune had removed all his difficulties ...'

And we note furthermore that the general's opinions are so well understood that the gentleman has refrained heretofore even from addressing her. The extreme unlikeliness of the events leading to this marriage, thereby permitting four people to marry the spouse of their choice, makes us even more aware of the unpleasant bitter taste behind this seemingly light and harmlessly entertaining Novel, as it is only too obvious that the usual process would involve years and possibly decades of suffering, and the strong possibility that one or more of the young people would be prevailed upon to marry 'advantageously', which is to say advantageous for the parent if not for the child.

' Never had the general loved his daughter so well in all her hours of companionship, utility, and patient endurance as when he first hailed her "Your Ladyship!" '

citations from Volume II Chapter Sixteen [ch 31 of 31]

What a repellent creature is Northanger Abbey's General Tilney. With the words, Never had the general loved his daughter so well, it appears to me that Jane Austen has figuratively lifted the Novel to the level of Greek myth and the story of King Midas, whose touch turned his daughter to gold. Because an inappropriate love of titles and social status is a constantly occurring theme in artistic treatments of Avarice — indeed of all the Deadly Sins beginning with Pride.

We see that Jane Austen is meticulous in demonstrating the failure in its objective of their avaricious (and invariably stupid) behaviour during the course of the Novel on all three of her illustrative characters:—

— For General Tilney: Should we give credit to the avarice of General Tilney, or to that of John Thorpe, for whipping the horses of the plot from simple explication into inexorable motion?

' Thorpe, most happy to be on speaking terms with a man of General Tilney's

importance, had been joyfully and proudly communicative; and being at that time

... pretty well resolved upon marrying Catherine himself, his vanity induced

him to represent the family as yet more wealthy than his vanity and avarice

had made him believe them ...

'... thankful for Mr. Thorpe's communication, [the General] almost

instantly determined to spare no pains in weakening his boasted interest and

ruining his dearest hopes. '

In fact, such success as the General has in seeing the ascension of his daughter to the ranks of the aristocracy, as well as to considerable fortune, is entirely inadvertent [and I still maintain such eventuality to be more plot contrivance than likelihood];

— For John Thorpe,

' irritated by Catherine's refusal, and yet more by the failure ... to accomplish a reconciliation between Morland and Isabella ... and spurning a friendship which could be no longer serviceable, hastened to contradict all that he had said before to the advantage of the Morlands ...'

citations from Volume II Chapter Fifteen [ch 30 of 31]

... spurning a friendship which could be no longer serviceable. Nine words, infinite knowledge, shrewdly summing up both John Thorpe and his sister Isabella. It's noteworthy that in spite of the great harm John Thorpe has caused in the life of the blameless Catherine Morland, he gains absolutely nothing as a result either of his avarice nor of his malice;

— For Isabella complete failure, after having been forced to apply, unsuccessfully, as it happens, to Catherine for assistance in finding her former fiancé James Morland whose fortune is suddenly rendered less contemptible when avaricious hopes of snaring Henry's brother Captain Frederick Tilney have come to naught. We recognise, although Isabella almost certainly does not, that losing the regard of Catherine and James Morland is of far greater account than anything she may have hoped to gain from a liaison with Captain Tilney, but the pretentious neither recognise nor value that which is genuine.

Of course, the efforts of the seasoned practioner of the Deadly Sin of Avarice are usually crowned with success rather than dunce's cap, the culprit in this case being John Thorpe, a pathological liar capable of inventing, believing, and convincing others of what he wishes to be truth, which is to say that Catherine Morland is rich beyond the wildest dreams of avarice, in the words of Mrs. Beverley in the second act of dramatist Edward Moore's The Gambler, always according to Wikipedia.

' The influence of the viscount and viscountess in their brother's behalf was assisted by that right understanding of Mr. Morland's circumstances which, as soon as the general would allow himself to be informed, they were qualified to give. It taught him that he had been scarcely more misled by Thorpe's first boast of the family wealth than by his subsequent malicious overthrow of it; that in no sense of the word were they necessitous or poor, and that Catherine would have three thousand pounds. '

Volume II Chapter Sixteen [ch 31 of 31]

If Pride and Prejudice is a honeybee savouring the delights of the English landscape from above, and Sense and Sensibility an immobile spider, then perhaps Northanger Abbey is a bird, a simple robin grateful for breadcrumbs and any other treats and nourishments scattered in its way.

It pains me somewhat to admit to a certain reluctant sympathy with Ralph Waldo Emerson, who admitted in his journals only to have read Jane Austen's first and last Novels, but still went on to complain:—

‘I am at a loss to understand why people hold Miss Austen's novels at so high a rate, which seem to me vulgar in tone, sterile in artistic invention, imprisoned in their wretched conventions of English society, without genius, wit, or knowledge of the world. Never was life so pinched and narrow. The one problem in the mind of the writer in both the stories I have read, Persuasion, and Pride and Prejudice, is marriageableness; all that interests in any character is still this one, has he or she the money to marry with, and conditions conforming? ‘Tis "the nympholepsy of a fond despair", say rather, of an English boarding-house. Suicide is more respectable.’

Ralph Waldo Emerson, quoting Byron with the "nympholepsy of a fond despair" line. — as found in the webpages of johnbyronkuhner.com

Imagine the private literary hand-wringing had Emerson added Sense and Sensibility and Northanger Abbey to his reading list. Of course we must remind ourselves that Emerson appears to lack a sense of humour, and not to understand the concepts of irony. (See the Wikipedia entry for Ralph Waldo Emerson for a description of what came to be known as his "Divinity School Address" at Divinity Hall, Harvard Divinity School, where Emerson discounted Biblical miracles and proclaimed that, while Jesus was a great man, he was not God — in other words, not divine. It would be as though a guest speaker at the Nobel Peace Prize deliberations had informed the committee that war and pestilence and famine are the natural state of humankind and to direct its efforts henceforth to the perfecting of warfare and the efficient bringing about of the other two catastrophic conditions.)

And yet Jane Austen, so detached and ironical, went to great lengths to invent happy endings for all her heroines; is it because we understand the improbability and sense the anguish underlying those fictional and perhaps contrived endings that we find ourselves on occasion reading Emerson with such sympathetic attention?

* * * * *

We are never quite certain if Jane Austen is giving her own thoughts, emotions, beliefs; or those impressions — possibly quite different — of the author's created characters; or even opinions invented for ironic effect. But surely we can give our trust to Jane Austen's authorly additions to a description of the progress of the rapidly developing friendship between Catherine Morland and Isabella Thorpe where the two

...

' shut themselves up, to read novels together. Yes, novels; for I will not adopt

that ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel-writers, of degrading

by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they

are themselves adding — joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing

the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read

by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn

over its insipid pages with disgust.

Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine

of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? ...

Although our productions have afforded more extensive and unaffected

pleasure than those of any other literary corporation in the world, no species

of composition has been so much decried ...

There seems almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing

the labour of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius,

wit, and taste to recommend them.

Northanger Abbey, Volume I, Chapter Five

On the other hand, she may be defending the writing of Novels in general, but I strongly doubt that the fastidious Jane Austen wished to recommend Ann Radcliffe's Gothic horror Novel Udolpho as a prime example of literary genius, wit, and taste.

"Have you gone on with Udolpho?" [Isabella Thorpe]

"Yes, I have been reading it ever since I woke;

and I am got to the black veil." [Catherine Morland]

"Are you, indeed? How delightful! Oh! I would

not tell you what is behind the black veil for the world! Are not you wild

to know?"

"Oh! Yes, quite; what can it be? But do not

tell me — I would not be told upon any account. I know it must be a skeleton,

I am sure it is Laurentina's skeleton. Oh! I am delighted with the book!

I should like to spend my whole life in reading it. I assure you, if it

had not been to meet you, I would not have come away from it for all the

world." '

Volume I, Chapter Six

I've already given several presumed reasons for Northanger Abbey's Gothic horror novel overtones; another possibility is that they help to illumimate the characters of Henry and Eleanor Tilney as Catherine continues to discuss Mrs. Radcliffe's Novel and to find sympathetic understanding in all minds except that of the thoroughly stupid John Thorpe. And while Thorpe succeeds in revealing his extreme artificiality whilst praising the very novel he believes he is condemning, Henry Tilney's obvious superior intelligence and education has given him no such pretentions.

' "But you never read novels, I dare say?" [Catherine Morland]

"Why not?" [Henry Tilney]

"Because they are not clever enough for you — gentlemen read

better books."

"The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel,

must be intolerably stupid. I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe's works, and most of them

with great pleasure. 'The Mysteries of Udolpho', when I had once begun it, I could not

lay down again; I remember finishing it in two days — my hair standing on end

the whole time ..."

"... I am very glad to hear it indeed, and now I shall never be ashamed

of liking Udolpho myself." '

And once we make the further acquaintance of Catherine's mother Mrs. Morland, we acquire a belated and more sympathetic understanding of Catherine's dismissal of history as a subject for light reading.

' "I can read poetry and plays, and things of that sort, and do not dislike

travels. But history, real solemn history, I cannot be interested in. Can you?"

"Yes, I am fond of history." [Eleanor Tilney]

"I wish I were too. I read it a little as a duty, but

it tells me nothing that

does not either vex or weary me ... You think me foolish to call instruction a torment,

but if you had been as much used as myself to hear poor little children first learning

their letters and then learning to spell, if you had ever seen how stupid they can be

for a whole morning together, and how tired my poor mother is at the end of it, as I am

in the habit of seeing almost every day of my life at home, you would allow that 'to torment'

and 'to instruct' might sometimes be used as synonymous words." '

citations from Volume I Chapter Fourteen

A good woman, Mrs. Morland, with no imagination and a thoroughly boring and prosaic understanding. I can think of nothing worse than learning to read from such a teacher. Nor do I imagine that that good lady's teaching of the potentially fascinating subject known as History would extend much beyond relevant dates, names, and geographical locations. We can thoroughly understand Catherine Morland's visceral need for escape into the realm of Gothic horror novels, and shudder at the 2007 Film's decision to constrict Catherine into the same button-mould as her mother. We've noticed that when Henry arrives at Fullerton to make his apologies and explanations to Catherine in Chapter 30, Mrs. Morland is upstairs searching for a certain improving essay intended to put her lovesick daughter in her place as the expression has it.

Once again, I can only deplore the 2007 film makers' decision to help Mrs. Morland attain this objective, anathema to all who believe that our lives, all lives, are a Fairy Tale journey toward fulfilment. And Fairy Tales are not only for girls; how often do stories for boys have a beautiful princess waiting for the hero to slay the fearsome dragon and prove himself worthy of the task?

It's strange to admit, but I experience no conflict between a profound rejection of the Film's ending and my serene conviction that when the youthful Jane Austen was writing Northanger Abbey, her mental picture of all the characters would be identical to the personages appearing in film two hundred years later.

* * * * *

I usually like to examine how the author has made use of literary Absences, or workings of the plot behind the scenes, and Henry's absence at the worst possible moment in Northanger Abbey is in my opinion not only one of the few believable happenings in the entire Novel but also an extremely effective structural decision.

Our loved ones are almost never there when most needed, and nor are we, perhaps, although that's not how things appear to us. On the other hand, the presence of Henry would have been highly inconvenient to the spirit and resolution of the plot of Jane Austen's Novel, where the reader has been dreading, almost from the moment when the execrable John Thorpe first whispers into the General's ear, the inevitable disclosure of the truth about Catherine's financial prospects.

And the fact that Mr. Morland was from home when Henry arrives, highlights Mrs. Morland's difficulties when at the end of a quarter of an hour she had nothing to say.

* * * * *

In the following section, my expectation is that I will discover as a result of more intensive reading of Jane Austen's charming unfinished Novel The Watsons, a dawning and reluctant realisation by the author that this format, this theme, these characters, this plot, all are insufficient for her purposes in revealing the progress of the Deadly Sin of Wrath. If, however, I prove myself to be mistaken, I hope to have the humility to admit the error and to go on to examine the manuscript more deeply.

Humility doesn't mean you think less of yourself. It means you think of yourself less.

Ken Blanchard

National Post, Quote

In A Box, Saturday January 18, 2014

Details of and links to all Austen-Novel Pictures are found either in the Pictures 3B or the present Pictures 3B Group II webpages.

This Page:—

Northanger Abbey Part Four: Architecture ... and Absences

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

The Somerset Room: Looking into the Square Dining Room and

Beyond to the Grand Staircase

Medium: Watercolour and bodycolour on paper

Dimensions: Support 139 x 189 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Reference D22735

On Loan to Art Gallery of South Australia (Adelaide,

Australia)

JMW Turner, ?exhibited 1795

JMW Turner, ?exhibited 1795

Title: Transept of Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire

Medium: Watercolour, graphite and pen and ink on paper

Dimensions: Support 355 x 260 mm

Collection: The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Turner Worldwide, Reference TW0689 Wilton 58

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

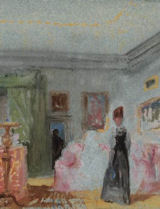

Title: A Bedroom: A Lady Dressed in Black Standing in a Room with a Green-Curtained

Bed — a Figure in the Doorway, 1827

Medium: Gouache and watercolour on paper

Dimensions: Support 138 x 192 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference: D22745 Turner Bequest CCXLIV 83

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

Title: The Grand Staircase: From the Bedroom Landing

Medium: Gouache and watercolour on paper

Dimensions: support: 143 x 187 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference: D22756 Turner Bequest CCXLIV 94

________________________