Pride and Prejudice is a Novel about giving, but also an examination of resentment, of anger, of baffled rage, and, ultimately, of liberating blind fury — all drawn from the warm side of the emotional spectrum.

The Novel Sense and Sensibility is about cold hard unrelenting fear; fear of loss: loss of control, loss of pride, of affection, of attention, of respect; fear of suffocation as all available oxygen is sucked out of the atmosphere by the insatiable unalterable demands of others; fear of genteel poverty, of being entirely dependent upon the generosity of others, of living every moment in the grip of the chill hand of incipient indigent death, of outliving or even losing one's paltry already insufficient income.

And of one potential manner of meeting such fear, which is to say, with envy pure and simple and its effects of diminishing, disparaging, and dismissing any and every one perceived as a threat.

And while the warm expansiveness of Pride and Prejudice

leads to its flourishing as a multiple-part, or even and especially

six-episode televised miniseries adaptation, the chill calculating

pretensions of Sense and Sensibility are equally and oppositely

benefitted by condensation into a two-hour film time frame.

* * * * *

Cover Art, DVD

Sense and Sensibility 1995

Whenever I meet the reproachful eyes of the characters on the cover of my personal DVD copy of the 1995 film, I feel like a bellowing bull amongst the most delicate porcelain in the china shop, and my ponderous musings about envy and deadly sin seem even to me to owe more to Pride and Prejudice's Mr. Collins than to the enchanting Elizabeth Bennet. And the reproach is merited, because from first scene to last of this film we are shown an Elinor Dashwood who is the embodiment of courage, affection, clear-sightedness, good sense, concern for others, and self-control (that last with one notable exception that shows unmistakeably how firm and at what cost has been that control). And necessarily free, of course, from Envy, or any other deadly sin.

All this, and as well a clearly-discernible theme, characters to illustrate it, and plot, whereby theme and characters are called upon to reveal their essence by action and reaction; by thought, and word, and deed — elements rare indeed in Novels, and infinitely more so in films of a mere two hours and a few minutes.

And as if that weren't sufficient, the 1995

film makes original and intelligent use of the most beautiful and

unusual English

poetry in order to further its aim of showing the course of the story.

I've mentioned previously that insofar as concerns the Novel Sense and Sensibility, the theme appears to me to waver between the need for moderation in all things and the wisdom of doing nothing:— which is to say that all things come to the person who waits. Perhaps surprisingly, perhaps not, both these sentiments are contained within the well-known citation from Ecclesiastes 3 [KJV] which I believe to be the theme of the 1995 film:—

1 To every thing there is a season,

and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

2 A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant,

and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

3 A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down,

and a time to build up;

4 A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn,

and a time to dance;

5 A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones

together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

6 A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep,

and a time to cast away;

7 A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence,

and a time to speak;

8 A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war,

and a time of peace.

It's noteworthy that each verse of the above citation contains its own

necessary opposite. And, to be fair, perhaps the Novel can be said

to be struggling fitfully toward such a theme, a mission statement it

never quite reaches.

The selection of film characters is as impeccable as every other choice in this film of challenges well-met and opportunities well-spent.

From the perfection of filmed Elinor Dashwood, to Edward, her ideal romantic foil; the 1995 Film has omitted Edward's visit to Norland Cottage, so that we are shown only his interactions at Norland before he is summoned away, purportedly by his mother. And yet we are given so much else that we almost never notice the omission, remembering only the manner in which cinema Edward acknowledges and gives evidence of great sensitivity toward the plight of his sister Fanny's unwanted in-laws. And his demonstrated kindness toward youngest daughter Margaret Dashwood, more child than adolescent in this incarnation, is sheer genius, her youthful assumptions and impulsive words propelling the action in the most natural possible manner.

And in spite of the alterations, Edward's friendship with Margaret in all honesty cannot be said to be sheer invention when we remember from the Novel his comments at Barton Cottage:—

"I wish," said Margaret ... "that somebody

would give us all a large fortune apiece!"

...

"What magnificent orders would travel from

this family to London," said Edward, "in such an

event! What a happy day for booksellers, music-sellers, and

print-shops!"

...

"You are very right in supposing

how my money would be spent — some of it, at least —"

[replied Marianne] "my loose cash would certainly be employed

in improving my collection of music and books."

"And the bulk of your fortune would be laid out ...

as a reward on that person who wrote the ablest defence of your favourite

maxim, that no one can ever be in love more than once in their life —

your opinion on that point is unchanged, I presume?"

"Undoubtedly. At my time of life opinions are

tolerably fixed. It is not likely that I should now see or hear any thing

to change them." [According to their mother, Marianne is

not yet seventeen!]

"Marianne is as steadfast as ever, you see,"

said Elinor, " she is not at all altered."

Sense and Sensibility, Volume I Chapter Seventeen

Funny. Playful. Sensitive. And yet prosaic in a manner that is lacking in the other more romantically-minded characters. What a good clergyman Edward would be, and fortunate indeed are parishioners young and old to be comforted in their seasons of trouble, and advised in times of decision by such an empathetic parson, who wishes only to do some good, in addition to giving short sermons — perfectly supported by the attractive reserve of the filmed Elinor, her reticence and smiling reluctance to insert herself into the lively inconsequential chatter of the younger members of the family.

The film's masterful touch of doing without the entirety of Willoughby's self-serving interview with Elinor results in his early relegation to the sidelines where he belongs, thus affording Marianne the opportunity to show a certain acquired maturity as she describes Willoughby's subsequent regrets had he chosen improvident marriage to Marianne rather than the fortune of Miss Grey. How much more effective, in art as in life, to have Marianne herself admitting Willoughby's waywardness as a liability in marriage, rather than the Novel's lecture from elder sister Elinor. And film Marianne's subsequent comparison of her conduct with Elinor's, and finding her own sadly wanting, is poignant where that particular bit of interaction in the Novel has always grated, on my sensibilities at any rate.

And streamlining the numerous Middletons into the interfering but generous and well-meaning pair of a bewigged old-fashioned Sir John and his mother-in-law Mrs. Jennings, causes the subsequent action and reaction to appear totally natural and inevitable. And Mrs. Jennings's daughter Charlotte and son-in-law Mr. Palmer add necessary heft to the story as a family with a young baby to protect from possible infection when visitor Marianne becomes desperately ill.

Meanwhile, Fanny Dashwood is joined in all her envy and hatefulness

by an almost equally jealous and spiteful Lucy Steele as the film's twin

villains — with the result that the film shows envy clearly and

unmistakeably, as an unworthy emotion to be scorned — entirely apart

and removed from the main protagonists of the film except as they are

forced to suffer its consequences.

As a rule, the discursive Novel tells and explains everything, while an adapted film's rapidly shifting and distracting images, sounds and movement show what they can of a plot, counting on the viewer to assign necessary meaning. Except that in the case of Sense and Sensibility, the Novel's haphazard structure confuses rather than enlightens, assigning equal length and importance to the most trivial as to the essential, so that extracting precious nuggets of fact from the fast flowing river of verbal and literary sludge is a feat worthy of the most experienced gold miner.

The true story of Colonel Brandon, his father and brother, his lost love and her daughter his ward, together with Willoughby's role in the latter's ruination, is thrown entirely into a single chapter of the Novel, where Brandon reveals all to Elinor, everything so jumbled together that the important facts are thrown to the winds of unintelligibility. Added to which Mrs. Jennings in the early pages is assigned the task of conveying the misinformation that Brandon's ward is his illegitimate daughter.

I could have hugged the screen when film Mrs. Jennings recounts to Elinor the true story of Colonel Brandon's lost love rather than the Novel's false stupidities. I still mourn the necessity of changing the young girl to a pauper, rather than her actual and far more interesting status as an heiress whose fortune is coveted by her guardian, Brandon's father, who forces her to marry the older brother and heir to the estate of Delaford. But even trying to untangle the story for purposes of the present paragraph demonstrates why and how the editing decision was imposed, and the intelligence and delicacy with which it is accomplished.

And the film of course has Brandon's story recounted all through the film, just as it should have been in the Novel. Particularly successful, I think, is the early invented scene in which the Colonel informs Sir John Middleton that

' "Marianne Dashwood would no sooner think of me than she would you, John ..."

Before adding with bitter emphasis:—

"And all the better for her." '

So that we are prepared for the realisation that in Brandon's view, he has failed in his duty to protect both the young women he cared for in life.

I have to assume that the film makers tried and found impossible

to make humourous Fanny Dashwood's manipulations in the opening scenes where she

convinces husband John to withhold from his stepmother and sisters the

assistance promised by John on his father's deathbed — scenes that

for some reason are funny as narrative but indescribably ugly

as purported reality. And the same is probably true of the

necessity to show literally Fanny's violent expulsion of

Lucy Steele after revelation of the latter's secret

engagement to Edward. Not funny at all.

One of the things I most dislike about the ending of the Novel Sense and Sensibility is the manner in which Marianne's marriage to Colonel Brandon is described almost as if she is trussed like a chicken by her family and served up to the Colonel on a platter, with only two tiny but remarkably beautiful phrases adding to our knowledge of what went before:—

'...

[Marianne] found herself at nineteen, submitting to new attachments,

entering on new duties, placed in a new home, a wife, the mistress of a

family, and the patroness of a village. '

(Paragraph 16)

'...

and that Marianne found her own happiness in

forming his, was equally the persuasion and delight of each

observing friend. Marianne could never love by halves; and her whole

heart became, in time, as much devoted to her husband, as it had

once been to Willoughby. '

(Paragraph 17)

Volume III Chapter Fourteen [ch. 50 of 50]

So much more is shown to us in the 1995 film, so much, and yet the structure is entirely thought out and organised, with the result that even though their marriage ends the film, Marianne and Colonel Brandon are indisputably the secondary coupling, after Elinor and Edward — the latter two against all odds truly representing Sense, and the others, Sensibility.

There is nothing trite in Shakespeare's Sonnet 116:—

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O, no! it is an ever-fixed mark ...

William Shakespeare, Sonnet CXVI

But its choice as material for the impecunious and improvident but handsome and dashing Willoughby to recite to not-yet-seventeen Marianne, drawing from his pocket seemingly spontaneously a tiny book containing the relevant text, marks him immediately as the ultimate seducer of every fond family's worst nightmares. His lips might be speaking of a marriage of true minds, but we suspect with reason that it's not her mind that most attracts him, and the impediments he is so blithely willing to dispense with are undoubtedly sacred vows and a wedding ring.

He might have used up an enormous amount of ink in Novel Elinor's interminable narrative, but John Willoughby's poetry and presence is very soon dispensed with in the 1995 film, at a distinct gain to coherence and dynamic forward motion.

Which brings the lover of English verse to Edmund Spenser, and Colonel Brandon. Unlike Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser (1552?-1599), received very little attention in the teaching of literature in my youth, and even my Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, Second Edition, published 1955, allots him two pages only.

We see Marianne Dashwood change slightly in the 1995 film, becoming rather more serious and definitely much smarter. But for real alteration, we need to examine the seemingly sedate Colonel Brandon. In fact, we are shown two separate and distinct Colonel Brandons, a phenomenon I tend to attribute to his taste in poetry. As regards that early, rather obsessive persona, I suspect that when alone the Colonel turns for comfort and torture, which amount to the same thing, to certain lines from Spenser's Amoretti and Epithalamion:—

My love is like to ice, and I to fire;

How comes it then that this her cold so great

Is not dissolv'd through my so hot desire ...

Or how comes it that my exceeding heat

Is not delay'd by her heart-frozen cold ...

What more miraculous thing may be told,

That fire, which all things melts, should harden ice;

And ice, which is congeal'd with senseless cold,

Should kindle fire by wonderful device!

Edmund Spenser, Amoretti and Epithalamion, Sonnet XXX

All very well. But when the bright-plumaged bird shows signs of approaching of its own accord, the wise fowler puts away nets and snares and plays a waiting game. And soon enough the elusive feathered creature is eating from the fingers of his hand, and flitting by to investigate the cage which has been furnished for its pleasure. And bird and catcher learn each other's ways as specific individuals rather than representations of a type.

And likewise perhaps Colonel Brandon has replaced Spenser's solitary Amoretti in search of more satisfactory lines, this time for sharing. And what better choice than the same author's The Faerie Queene: Book 5: Canto II, which begins with the knight being assured that the fairest lady has been found, safe returned to health and happiness? We've always known, even from the Novel, that Marianne's heart is going to be won by way of the Colonel's well-stocked bookshelves, and her determination that:—

' "When the weather is settled, and I have recovered my strength ... I know we shall be happy. Our own library is too well known to me, to be resorted to for any thing beyond mere amusement. But there are many works well worth reading ... which I know I can borrow of Colonel Brandon. By reading only six hours a-day, I shall gain in the course of a twelve-month a great deal of instruction which I now feel myself to want." '

Sense and Sensibility, Volume III, Chapter Ten [ch. 46 of 50]

There is something very interesting in the Colonel's reading to Marianne near the end of the Film, irresistible for lovers of esoteric detail. When first we see them, he is reading the beautiful lines calling upon the evil Gyant if he be so wise, to take his ballaunce [scales] and weigh the wind, or weigh the light, that in the East doth rise;

Or weigh the thought, that from man's mind doth flow.

But if the weight of these thou canst not show,

Weigh but one word which from thy lips doth fall.

But while Elinor and their mother are watching from the window, and speaking of the scene before them, the Colonel has turned back a page or two to re-read a favoured passage:—

... It is no more at all:

Nor is the earth the lesse, or loseth aught,

For whatsoever from one place doth fall,

Is with the tide unto an other brought:

For there is nothing lost, that may be found,

if sought.

Quotations from Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, Book 5: Canto II

Willoughby is wild and extravagant in all that he does both in Novel and in film, while film Colonel Brandon, paradoxically, is the more theatrical. Age and experience have imparted discipline, of course, but from his manner of speaking to the way in which he moves, and walks, and inhabits his clothes, his boots — the Colonel has a dramatic flair which ought to be pleasing to Marianne's romantic inclinations.

The reading of Spenser's lines above is followed by Colonel Brandon's reply that he will be unable to continue the next day, as suggested by Marianne.

"Away? Where?" demands his lady, a markedly imperious tone to her voice.

But now she is dealing with the real Colonel Brandon, no longer helplessly besotted, but entirely in command of himself, of the situation.

And where Sense and Sensibility the Novel is burdened with one inexplicable unexplained announcement of imminent departure after another, the Colonel's "It's a secret," is followed by the delivery of a small enough instrument to fit the parlour, and the news that he will be returning the next day. So that when a male rider is seen approaching, everyone including the viewer assumes that we know his identity, lending a jolt of surprise to the fact that the rider is Edward, supposedly married to the mercenary Lucy Steele. In other words, the best kind of literary absence, for every right reason.

And I believe that Elinor's breakdown into uncontrollable tears and sobbing when she learns that the Mr. Ferrars who has married Lucy, is Edward's younger brother Robert, demonstrates more than any possible words the unbearable and unrelenting strain under which she has been labouring these many months, having to remain strong for the sake of weaker more demonstrative mother and sisters — until the pressure at long last is released with the discovery that Edward is free and has come to declare his love and ask her to marry him.

But an earlier interaction where Mrs. Dashwood cries at the cruelty and injustice of it all while a forlorn Elinor ineffectually pats her mother's shoulder is even more revelatory, since it demonstrates the dilemma of an eldest child and the feelings of responsibility both to parent and younger siblings. And affords me, as an eldest daughter, the opportunity to affirm that here is the model of what it is to be the eldest sister. While the Novel's heroine/narrator is the portrait not of elder-sisterliness, but a demonstration of unredeemed Envy pure and simple.

Redemption ... I am reminded of the ending of Paul Kokoski's English language Pravda.ru webpage and his suggested remedy to counter the painful pangs of Envy, that most joyless of the Seven Deadly Sins:— Emulation!

... For emulation to be good and remain free from envy it must be

1) right in its object, i.e. it must bear not on the successes

but on the virtues of others so as to imitate them

2) worthy in its motives, seeking not to vanquish others,

humiliate them, bring them under subjection, but to make us

better

3) it must be fair in the means it employs to attain its end;

not intrigue, not subterfuge

Emulation is an effective remedy against envy because

it causes no one harm and is, at the same time, an excellent

stimulus.

Paul Kokoski, Pravda.ru — Envy: Most joyless of Seven Deadly Sins (Paragraphs 13 and 14)

It appears to me that creative people enjoy unlimited opportunities to rid themselves, through emulation, of destructive envy; any object that might arouse envy can be copied, adapted for personal use thus becoming uniquely their own:— clothes, furniture, jewellery, even personality traits. I don't see how adapting what we envy to our own uses can possibly run counter to the above stipulations. Isn't imitation said to be the sincerest form of flattery?

And although Kokoski never mentions competitiveness by name as part of emulation, it seems that here we might find one virtue relating to the Deadly Sin of Envy. Without the spur of beauty, taste, characteristics, or accomplishments of others, how are we even to know what is available for us to aspire to? Had Sense and Sensibility the Novel's Elinor Dashwood possessed the courage and honesty to acknowledge and accept her resentment at the unfairness of the necessity to compete with lovelier and more desirable sister Marianne, she might well have become exactly what we see in the 1995 filmed version described above. Because we all have to compete, for attention, for time, at home and in the world, and if there is no one about to measure ourselves against, we compete with ourselves, against yesterday's imperfect shadow.

And what more joyful way to reassure ourselves that all is not wrong with a universe in which our neighbour is unjustifiably enriched than to remember the 1995 Elinor Dashwood, and the exquisite sensitivity that went into such a portrayal of infinite love and acceptance.

* * * * *

In my opinion, the entire Novel Sense and Sensibility is a parody or caricature, to begin with of Austen's first and greatest Novel Pride and Prejudice, secondly of the Fairy Tale East of the Sun and West of the Moon which I consider most similar in mood and structure to Pride and Prejudice the Novel, to say nothing of the Myth Amor and Psyche — itself a parody (or so I believe) of the said Fairy Tale.

In the Fairy Tale East of the Sun and West of the Moon, the white bear receives the love of the girl, when she holds up the candle while he sleeps and is enabled to see him as he truly is. But he has been wakened by falling wax from the forbidden candle, and flies away to a place inaccessible to her.

She sets out to find him on the purposeful journey which is the hallmark of Fairy Tale, and the path is strewn with people, creatures and entities such as the four winds anxious to lend themselves to her service. All greet her with the same haunting words: 'You're the one who is meant to have the prince!' The girl meets entities, gifts and offers of assistance with the blissful acceptance of childhood. Much in the way of hardship attends her journey, but she is undaunted in her determination to track down and rescue the prince who is being held in a castle by a wicked witch (and stepmother) determined that he marry her ugly daughter.

Then there is Sense and Sensibility the Novel, whose heroine/narrator Elinor denies being on any kind of journey and lauds the preferability of doing nothing at all, culminating in a meeting with wicked witch Lucy Steele and the latter's announcement that she's the one who is meant to have Edward.

In the Fairy Tale, the girl puts herself into great danger and uses all necessary subterfuge to have herself admitted to the castle, where she rescues the prince by bringing him to his proper senses. In the Novel, even though Elinor is convinced that Lucy cares nothing for Edward nor Edward for Lucy, and also that Edward loves only her, Elinor takes pride in leaving him to his own pitiful resources, making no effort even to communicate with the unfortunate presumed hero of the tale.

And if that's not caricature enough, it soon becomes apparent that Elinor has convinced herself that the prince she is meant to have is Colonel Brandon, who is as constant and faithful and rich as Edward is slippery and elusive and poor, and has the Fairy Tale advantage of owning a shining manor estate and kingdom named Delaford. And the purpose of the caricature fairy tale is aimed at demonstrating the superiority of Elinor and her predestined right to possess Delaford, the Colonel's attractive manor estate, if not the Colonel himself.

Except that the constancy and fidelity and wealth of Colonel Brandon is reserved for Elinor's totally unworthy younger sister Marianne, who considers him too old and boring to be an authentic hero and much prefers Willoughby, the young and handsome but loathsome dragon Colonel Brandon has been trying to slay for years.

And Colonel Brandon is on a true Fairy Tale journey of his own, being a younger son who has inherited Delaford unexpectedly upon the death of his elder brother. An elder brother who has been forced to marry Brandon's first love, an heiress whose guardian is Brandon's father.

But Colonel Brandon's story, like Marianne's, is surrounded by such a thicket of impenetrable words and phrases that we are unable to grasp its essential meaning. In fact, the Colonel's entire story, encompassing his birth as a younger son to the present, is condensed into one single plot-driven meeting with Elinor in Chapter 31 which leaves heroine-narrator Elinor sufficient time and space to concentrate on the important matters of the Novel such as they are, in her estimation.

Colonel Brandon, who had a general invitation to the house, was with them almost every day; he came to look at Marianne and talk to Elinor, who often derived more satisfaction from conversing with him than from any other daily occurrence, but who saw at the same time with much concern his continued regard for her sister. She feared it was a strengthening regard. It grieved her to see the earnestness with which he often watched Marianne ...

Sense and Sensibility, Volume II Chapter Five [ch. 27 of 50]

Envy is certainly not unknown in Fairy Tale, Hans Christian Andersen's The Soldier and the Tinderbox being almost entirely envy revenge fantasy, but there is still a certain innocent amorality that robs the tale of malice, even as the Soldier kills the king and queen, the Princess's mean parents who stand in his way, and hers. There is nothing childlike in the Novel Sense and Sensibility, and the malice preventing the fairy tale story being told is impossible to ignore. Naturally, we would forgive the omission had we an alternative better fairy tale to engage our interest, but in fact only a pale uninteresting non-story is offered in place of the blocked and hidden narrative which has been withheld.

Both Mrs. Jennings and their brother John believe that Colonel Brandon loves and wishes to marry Elinor, which should lend a certain suspense to the prceedings. It doesn't, mainly because we know it's Delaford and not Brandon that Elinor covets. Similarly, the awkward page-consuming machinations regarding the elopement of Lucy Steele and Mr. Ferrars — actually Edward's brother Robert — are drawn out over so many chapters and told from so many points of view that there is no space remaining for anything else.

As for Myth, a differently-written Novel might have aroused our sympathies for this family, exiled from their family home through no fault of their own. Except that the tears and lamentations of the heartbroken Mrs. Dashwood and Marianne are treated as unhinged hysteria, while Marianne's occasionally expressed longings for the scenery of her former home are treated as additional proof of regrettable instability rather than fodder for mythic tragedy.

I've said previously that there is almost no overt similarity between Lucius Apolonius's Myth Amor and Psyche, and the Novel Pride and Prejudice other than the Myth's eloquent portrayal of the insouciant Amor/Cupid arriving at Psyche's house intending to carry out his mother's injunction to wound Psyche with one of his arrows so that she will fall in love with the ugliest creature imaginable, and thus be rendered ridiculous in the eyes of men — and upon beholding Psyche accidentally wounding himself and becoming his own unintended victim — not entirely unlike the fate of the arrogant Mr. Darcy.

On the other hand, if we forget Amor and concentrate on the ferocious jealousy of Venus — Behold, I, Venus, the kindly mother of all the world — who sends the blameless Psyche to perform a number of tasks meant to destroy the beauty which has cast that of Venus into the shade, I believe an argument might be made for a certain likeness in form between Myth and Sense and Sensibility the Novel.

* * * * *

With an income quite sufficient to their wants thus secured to them ...

the [marriage] ceremony took place in Barton church early in the

autumn.

Mrs. Jennings ... was able to visit Edward and his wife in

their Parsonage by Michaelmas, and she found in Elinor and her

husband, as she really believed, one of the happiest couples in

the world. They had in fact nothing to wish for, but the marriage

of Colonel Brandon and Marianne, and rather better pasturage for

their cows.

Volume III, Chapter Fourteen [ch. 50 of 50]

And rather better pasturage for their cows. Envy, of course, can never acknowledge itself to be satisfied — The covetous man is ever in want: (Horace) — and when Colonel Brandon, or even the obliging Mrs. Jennings, has rectified the insufficiency of pasturage, I'm sure Envy and Elinor between them will have thought of something new to wish for. And get, though never undisputed possession of the manor house she so covets.

In one of those ironies of life that so bemused the ancient Greeks, and for all that she so yearns for it, Elinor is exactly the sort of person who would be totally unsuited as lady of the manor. For all her faults, and they are legion, Pride and Prejudice's Lady Catherine de Bourgh demonstrates the expansive personality, interest in other people, and what might be called noblesse oblige to deal with servants, gardeners, needy tenants, pensioned former employees, worthy parsons and their wives and families, visiting family members and their friends, and all the other personages housed within the boundaries of Rosings, her estate.

I don't envisage chilly evasive retentive Elinor as possessing the warmth and generosity — the largeness of outlook — to be capable of the delegating of power that would be essential in such a role. Nor is she farsighted enough to understand the implications of her brother John's admittedly hilarious explanation of having to use money that is owed to the Dashwood ladies in order to buy certain property that has come onto the market. Nor do I see her deferring to the opinion of a husband or steward who might be presumed to know better than she that you can't always take, but are sometimes obliged to give.

I suppose it's unforgivable of me, but in fact I believe that on Elinor's own admission, Barton Park's Lady Middleton is far more suitable than Elinor to be a perfect lady to the manor born. (And this in spite of the fact that Lady Middleton's parents Mr. and Mrs. Jennings belong resolutely and unashamedly to the rich business class. )

Lady Middleton piqued herself upon the elegance of her table, and of all

her domestic arrangements; and from this kind of vanity was her greatest

enjoyment in any of their parties.

[Chapter Seven]

Lady Middleton was more agreeable than her mother,

only in being more silent. Elinor needed little

observation to perceive that her reserve was

a mere calmness of manner with which sense had

nothing to do ... Her insipidity was invariable, for

even her spirits were always the same; and though she

did not oppose the parties arranged by

her husband, provided every thing were conducted

in style and her two eldest children attended

her, she never appeared to receive more enjoyment

from them [the parties, presumably], than she might

have experienced in sitting at home ...'

[Chapter Eleven]

It doesn't seem to occur to Elinor that perhaps Lady Middleton doesn't like her husband inviting his distant relations into their home every day that he is not arranging parties on their behalf; that Lady Middleton might be perhaps aware of the contempt in which she is held by her husband's needy extended family.

Nor could any mother as fond as Lady Middleton fail to observe Elinor Dashwood's dislike of children, which seems to be exceeded only by her antipathy toward any mother so lacking in merit as to prefer the company of her children to visitors such as the Dashwood females.

And yet in fact the Novel Sense and Sensibility does seem to end happily in a bittersweet victory by Elinor Dashwood over Lucy Steele, betrothed to Edward until a decidedly better prospect comes along when she elopes with his younger brother Robert, leaving Edward free to marry Elinor at last.

Pretentious people are said to pride themselves on attributes they don't really have, whilst ignoring or at least downplaying those lesser virtues or advantages they do possess. In the final paragraph of that final Chapter 50, and therefore of the Novel, heroine/narrator Elinor Dashwood announces with great pride that

... Among the merits and the happiness of Elinor and Marianne, let it not be ranked as the least considerable, that though sisters, and living almost within sight of each other, they could live without disagreement between themselves, or producing coolness between their husbands.

Just as Colonel Brandon's entire life story is condensed into Chapter 31 so that no one item is distinguishable from another, so is the true story of Lucy Steele's snaring of Edward's brother Robert inserted into an interminable paragraph 11 of said final chapter 50. How easy it is to miss the significance of the final few lines of that paragraph 11, as expressed by Austen at her most witty and caustic:—

... Setting aside the jealousies and ill-will continually subsisting between Fanny and Lucy, in which their husbands of course took a part, as well as the frequent domestic disagreements between Robert and Lucy themselves, nothing could exceed the harmony in which they all lived together.

Elinor obviously believes that the celestial harmony subsisting at Delaford at the end of the Novel is due to that strength of understanding, and coolness of judgment, which qualified her, though only nineteen, to be the counsellor of her mother [Chapter One, Paragraph 11]. I would suggest, perhaps ill-manneredly, that Elinor is fortunate in living in close proximity with three extremely sweet-natured persons. And that she is given her own way in spite of rather than because of her assumed superior powers. And whereas self-interest is at work in any dealings between Lucy and Robert, and Fanny, and Mrs. Ferrars, affection is the guiding principle reigning at Delaford.

Who could ask for more? — And since her mother Mrs. Dashwood was prudent enough to remain at the cottage [Final chapter Volume III, Chapter Fourteen, Paragraph 20 of 21], Elinor has at last found herself in that one place where she belongs, free from interference from others whilst free herself to interfere, to advise, to supervise; to spend as little and save as much as possible; to make do; to be happy in fact, as well as in the opinion as she really believed of the frequently ill-informed Mrs. Jennings.

________________________

Details of and links to all Austen-Novel Pictures are found in the Pictures 3B webpage.

This Page:— Sense

and Sensibility Part Three: Film, Fairy Tale, and Happily Ever After

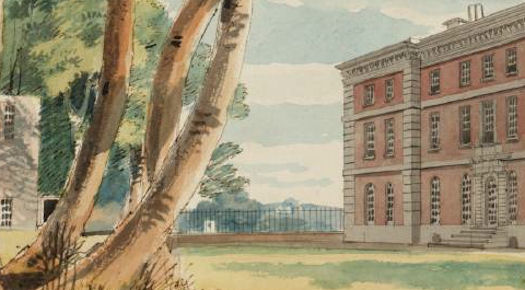

JMW Turner, 1789

JMW Turner, 1789

Title: Radley Hall from the North-West 1789

Medium: Pen and ink and Watercolour on paper

Dimensions: support: 374 x 532 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference: D00048, Turner Bequest III C

JMW Turner, 1789

JMW Turner, 1789

Title: Radley Hall from the South-East 1789

Medium: Watercolour on paper

Dimensions: support: 330 x 510 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference: D00049, Turner Bequest III D

Cover Art, DVD

Cover Art, DVD

Amazon.com Sense and Sensibility 1995 Special Edition

also

Wikipedia, Film Sense and Sensibility 1995

also

The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations:—

Movie Locations Sense and Sensibility 1995

________________________