With the cornerstone of Chapters One and Two in place, comes the necessity for fresh materials befitting the foundation of a structure destined to be a great mansion. Additional characters are required to interact with, and build upon our knowledge of, the members of the Bennet family; action is needed to carry out the intentions of the dialogue, as well as new venues to offer scope for the narrative. Chapter Three of Austen's novel will provide the framework of that foundation.

In fact, Chapter Three signals immediately that construction of the novel has been lifted onto this higher plane. Gone are the terse paragraphs of no more than a line or two of dialogue; now we are given lengthy blocks of exposition, and dialogue has been sharpened to concern the intentions of the immediate scene rather than simply revealing character. We are so anxious to meet Mr. Bingley, the young man of large fortune whose entry into the neighbourhood has cast Mrs. Bennet and her daughters into such pleasurable confusion, that we are inclined to skim past the chapter's opening lines without taking a moment to savour their delicious modernity.

NOT all that Mrs. Bennet, however, with the assistance of her five daughters, could ask on the subject was sufficient to draw from her husband any satisfactory description of Mr. Bingley. They attacked him in various ways; with barefaced questions, ingenious suppositions, and distant surmises; but he eluded the skill of them all.

* * * * *

Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice was published at the beginning of the nineteenth century. At the beginning of the twenty-first, is it any easier to prevail upon someone of the masculine species to give us a decent description of the appearance of another male? That is to say, whether or not he is handsome? Yet still they manage to elude the skill of us all.

Part of the reason we miss the modernity of that observation is our bemusement with the strictures of propriety which demand that Mr. Bennet visit Mr. Bingley at his home before the Bennet daughters can be permitted to hope to meet him, or even to know what the eligible bachelor looks like.

'Indeed you must go,' says Mrs. Bennet in Chapter One, 'for it will be impossible for us to visit him, if you do not.'

In the Novel, as in life, certain men will offer their opinion on any subject. Fortunately for Mrs. Bennet and her daughters, Sir William Lucas is one such man, and the remainder of Chapter Three's opening paragraph tells of Lady Lucas's highly favourable report of Mr. Bingley's wonderfully handsome appearance, extremely agreeable personality, and delightful intention of attending the next assembly ball in the company of a large party.

Before we finally meet Mr. Bingley in person we are treated to Jane Austen at her most delicately ironic: as the news of Mr. Bingley's planned attendance at the assembly ball travels through their small neighbourhood, Mr. Bingley's large party becomes twelve ladies and seven gentlemen, a surfeit of females which grieves the Bennet girls, who are, however, comforted the day before the ball by news that Mr. Bingley had brought from London only ...

... his five sisters and a cousin. And when the party entered the assembly room it consisted of only five altogether, Mr. Bingley, his two sisters, the husband of the oldest, and another young man.

That 'another young man' is, of course, Mr. Darcy, and his words and actions at Chapter Three's Assembly Ball will affect every succeeding page of the Novel. His pride gives rise to no small reactions of wounded pride and intense prejudice on the part of Elizabeth, the object of his studied insult. Studied because Austen makes clear that Mr. Darcy is aware that Elizabeth is listening when he tells Bingley that Elizabeth:

'... is tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me; and I am in no humour at present to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men.'

When watching the building of a foundation we can never be certain what it is to support until construction of the ground floor and upper storeys is well under way. We will have much more to say about Mr. Darcy's fatal pride, as illustrated in this scene, at a later time, when the plot permits us to see where it leads. (In fact, we will have much more to say than Jane Austen does, a deficiency I once blamed almost entirely on Mr. Darcy's lack of candour.)

But Chapter Three offers in addition to Mr. Darcy a surfeit of essential information. Every character with the exception of Mr. Bennet attends the ball; and Mr. Bennet appears at chapter's end. Characters continue to reveal themselves in all their simple complexities:

Mr. Bingley: good looking and gentlemanlike; with a pleasant countenance, and easy unaffected manners, dancing every dance, angry that the ball closed so early, and talking of giving one himself at Netherfield.

Mr. Hurst, husband of Mr. Bingley's sister Louisa, who merely looked the gentleman;

Mr. Darcy: a fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien ... looked at with great admiration for about half the evening, till his manners gave a disgust ... for he was discovered to be proud, to be above his company, and above being pleased.

Elizabeth: who

... remained with no very cordial feelings toward him [Mr. Darcy, of course]. She told the story however with great spirit among her friends; for she had a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in any thing ridiculous.

Jane: as much gratified as her mother could be, though in a quieter way. Elizabeth felt Jane's pleasure.

After the cavalier manner in which she has been treated by Mr. Darcy, Elizabeth shows remarkable sisterly love in sharing Jane's pleasure at being invited to dance — twice — by Mr. Bingley [although not even sisterly affection overcomes quiet skepticism as to the worth of Jane's having been distinguished by the notice of Mr. Bingley's elegant sisters, as we soon discover in Chapter Four].

And what to say of the distinctive peculiar contrariness of Mr. Bennet:

... on the present occasion he had a good deal of curiosity as to the event of an evening which had raised such splendid expectations. He had rather hoped that all his wife's views on the stranger would be disappointed.

Mrs. Bennet to her husband:

'Jane was so admired, nothing could be like it ... First of all, he asked Miss Lucas. I was so vexed to see him stand up with her; but, however, he did not admire her at all: indeed, nobody can, you know'.

(Miss Lucas being Charlotte, Elizabeth's intimate friend. Have we read anywhere a more vicious remark dropped into casual conversation?)

Because her husband refuses to listen to a description of the finery of Mr. Bingley's sisters, Mrs. Bennet instead relates, with much bitterness of spirit and some exaggeration, the shocking rudeness of Mr. Darcy,

'... a most disagreeable, horrid man, not at all worth pleasing. So high and so conceited that there was no enduring him! He walked here, and he walked there, fancying himself so very great! Not handsome enough to dance with! I wish you had been there, my dear, to have given him one of your set downs. I quite detest the man.'

The reader has no choice but to wonder which of the two masculine newcomers is to suffer most: the gentlemanly Mr. Bingley from Mrs. Bennet's fawning approval, or the 'most disagreeable, horrid' Mr. Darcy from her violent detestation.

Insofar as film is concerned, I was bewildered that the 1940 film had Darcy soften the insult to a reference to Elizabeth's middle class social standing rather than her lack of sufficient beauty.— Until some time later when I realized that the film's more bizarre alterations from the Novel were all of a kind and owed much to contemporary admiration of Neville Chamberlain's political negotiating style. What other possible explanation could exist for a decision to turn Lady Catherine de Bourgh, the Novel's fairy tale witch, into Cinderella's fairy godmother than a conviction that being 'nice' will conquer all terrors?

With the comparatively lengthy Chapter Three, Austen has laid the framework of the foundation of her stately mansion. Each of the next nine chapters of Pride and Prejudice deals with the inevitable aftermath of that fateful Assembly Room ball, and completes the foundation by providing more narrowly focussed literary beams and reinforcing structures. Once the foundation is completed, Chapter Thirteen will demonstrate that it has ascended to a higher level by way of the previously constructed staircase, to the ground floor with its doors through which new characters can make their entry, and windows to illuminate the Novel's widened story line.

* * * * *

Pictures 3A

With the exception of the Hubble Footer,

most Pictures on these Pride and Prejudice and other

Austen webpages, are from the

Turner Bequest of the Tate Museum

Collection Online.

This Page Chapter 3, Foundation (1)

The Meryton Assembly

JMW Turner, circa 1818

JMW Turner, circa 1818

Title: Farnley in the Old Time

Medium: Bodycolour on paper

Dimensions: unconfirmed 278 x 393 mm

Private Collection, Turner Worldwide

Reference: TW0262, Wilton 629

JMW Turner, ?1798

JMW Turner, ?1798

A Gothic Arch in Mr. Wyndham's Garden at Salisbury, ?1798

Medium: Gouache, graphite and watercolour on paper;

Dimensions: Support 477 x 329 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D02350

JMW Turner, 1827

JMW Turner, 1827

East Cowes Castle, A Vaulted Passage 1827

Medium: Chalk and pen and ink on paper;

Dimensions: Support 191 x 140 mm

Collection: Tate, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

View by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints

and Drawings Room

Reference D20813

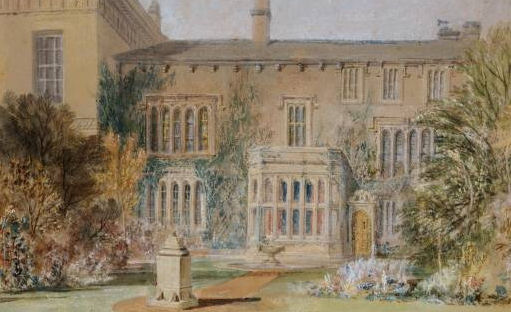

JMW Turner, 1815

JMW Turner, 1815

Title: The East Front ["Garden Front"] of Farnley Hall, with the Flower Garden

and Sundial

Medium: Bodycolour and chalk on paper

Dimensions: unconfirmed 303 x 403 mm

Private Collection, Turner Worldwide

Reference: TW0239, Wilton 586

________________________