Introduction 2B

Myth, The Source of all* Storytelling

(*All, except Fairy Tales.)

If every Fairy Tale is a journey,

Myth is an effort to make sense of where we

find ourselves at journey's end.

Making sense presupposes an ability

to reason. Reasoning assumes the capacity to think.

And thinking involves the use of words, those marvellous

and mystical, unseen and unique life-altering entities

sometimes unkindly described as lies.

If Fairy Tales tell us who we are,

Myth is the raiment — the tissue of falsehoods,

misdirection and concealment — with which we cover

up our frailties and flaunt our attributes.

Just as we demand from Fairy Tales certain

characteristics in order to qualify for the title, so Myth

has its own essential elements, often ascertained in

direct opposition to Fairy Tale, and beginning with the

latter's Transformatory Journey:—

- To begin with, there's no Once upon a time

in Myth. Fairy Tales are

told to us; we read Myth

alone. Freed from dependence upon adult benevolence

for our entertainment — and everything else — we lose the

perception of our solitariness, and our helplessness as well.

No longer needing the security of Once upon a

time, we are enabled by Myth

to move on to the uncertainty of more universal

themes.

- Secondly, Fairy Tales' Happily ever after does

not mean growing up. If Fairy Tales are about a hero

or heroine who remains constant amid a journey of continued

and shattering change, Myth

concerns a more or less adult protagonist caught

in static and implacable forces that forever

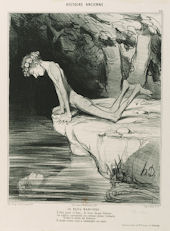

alter him or her. Narcissus,

and Apollo and Daphne

come to mind, because what could be more static

and rooted than a flower, or a tree?

— The fate of

Narcissus can be

understood as a simple narrative, as a small morality

tale on the dangers of loving oneself so thoroughly that

we become fixated on our reflected glory to the exclusion

of everything else, or as an analytic tool to describe

the workings of a severe neurotic disorder, depending

upon the capacity for intellectual sublety on the part of

the reader.

— The fate of

Narcissus can be

understood as a simple narrative, as a small morality

tale on the dangers of loving oneself so thoroughly that

we become fixated on our reflected glory to the exclusion

of everything else, or as an analytic tool to describe

the workings of a severe neurotic disorder, depending

upon the capacity for intellectual sublety on the part of

the reader.

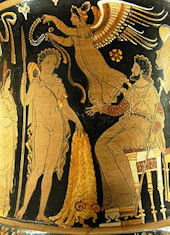

—Apollo and Daphne

is capable of even deeper complexity of meaning, from our

natural repulsion toward an overly enthusiastic pursuit

by an unwanted lover, to the psychological phenomenon of

figuratively turning ourselves into unresponsive wood

when submission to superior physical force is

unavoidable. And all this effected by the use of

words as the medium of transformation, rather than

of narration.

________________

- Aloneness. In Hansel and

Gretel, brother and sister are both

capable of the detachment necessary to see the sibling as

a fully rounded person, shockingly uncharacteristic of a

Fairy Tale, though not entirely uncommon for Myth.

One way in which multiple points of view are shown

in Myth is through the use of

multi-episode narratives, containing mostly the same cast

of characters but from the perspective of a different

protagonist for each section — unthinkable in Fairy

Tale. (Reading

Homer, watching Star Trek; what more could anyone

ask of life? Or of Myth?)

- Prototype versus uniqueness of character. Fairy Tale

characters are unique by virtue of their circumstances

and the detail which surrounds each story. Myth

will involve prototypes: Little

Red Riding Hood versus Prometheus, for example.

- Acceptance of Change. By the time we are

ready for Myth

we have gained sufficient confidence to contemplate with

equanimity the prospect of change, in ourselves as well as in

our circumstances.

- Strangers along the route. Strangers

along the route

of a Fairy Tale generally exist in order to facilitate

the unfolding of the plot. Strangers in Myth

are the plot, with their warnings

and foreshadowings, their pursuits and strategems and

their trickery. Strangers may disappear in Myth,

but we have always the strong suspicion that they will come back

as soon as a hero becomes comfortable in his or her situation.

- Creatures with magical powers.

In Myth,

magical creatures such as witches, ogres, dragons, trolls

and the occasional fairy are often replaced by gods and

goddesses, not always an improvement for the fate of mortals

awaiting their erratic but implacable pleasure.

- Detail. Without its inseparable detail,

there is no Fairy Tale. Myth being a

creation of words used to convey complex ideas rather

than simple narrative, its details can be omitted, added

to, mocked, converted to lyrics, confused with historical

fact, and otherwise manipulated at will.

- Truthfulness: There's no lying in

Fairy Tale. Children hearing a Fairy Tale have no reason

to doubt its essential truthfulness. Myth,

on the contrary, existing simultaneously on many

different planes, can be, and frequently is, subject to

immense variety in interpretation.

- Irony: There's no irony in Fairy

Tale. And one of the signs that

a child is ready to move up from comfortable Fairy Tale

to unsettling Myth

is the development of the ability to appreciate the

delicious properties of irony.

- Innocent amorality: There's no right

and wrong in Fairy Tale. If Fairy Tales are marked by an

innocent amorality, we see in Myth the beginnings of

a higher authority to whom a wronged mortal can appeal for justice:

all-powerful Zeus, greatest of the Olympian gods, is often shown as

solicitous of the well-being of mortals in need of his assistance and support

— although in cases where wrongdoing involves Zeus himself, things

frequently become more complicated.

- Tolerance: There's no preaching in Fairy

Tale. A fable, with its prim lessons

and worthy instruction, is never a Fairy Tale, but can

often be a Myth, where words

are used as much to conceal, instruct, and misrepresent

as to narrate:— Atlas, for example,

tricked into holding the world on his strong shoulders,

and accepting the necessity of continuing the job because

there is no one else to do it, never could be presented as

a character in a Fairy Tale. Nothing is demanded of the Fairy

Tale listener but undivided attention, and the concept of duty does

well to wait for a mind more suited to the complexities

of Myth.

- Subterranean Meaning. Meanings in Myth

are hidden and sophisticated, but unlike Fairy Tale we

sense at least a seeming effort to make some kind of

sense of life's enduring mysteries. (Why should one

person die in infancy, for example, while another lives

to be 100? For ancients the answer is as simple as the Myth

of The Moirae, three white-robed Spinners, one of

whom, Atropos, decides on the

manner of death of each mortal being, cutting the thread

of life with her shears when she decides it's time.)

- — This in contrast to Fairy Tales, which are

themselves the

unrevealable mystery.

* * * * *

In conclusion:

— If

it's true that all storytelling is based upon

Fairy Tale and/or Myth,

then it should be possible to examine our five chosen

artistic works in conjunction with at least one

particular representative of the assumed source.

Except that I've already proven

the rule by exception with Dear Frankie,

neither Fairy Tale nor Myth, but just itself.

Meanwhile Blackpool

so successfully proves my rule that I've been forced

to deal directly with relevant Fairy Tale and Myth

in my treatment of the six Episodes of that BBC

television miniseries.

Fortunately I've been more

successful in separating Pride and Prejudice

from its possible Fairy Tale and Myth forebears,

beginning with Fairy Tales and

Pride and Prejudice in the next section.

[July 2007, text only

WebPage last amended

February 22nd, 2013]

________________________

-

Top of this Page

- Introduction 2B:—

Myth

-

Main Page – Index

- Main Page – Index

-

HomePage-2

- HomePage-2

Fairy Tale and Myth

-

Previous Page

- Introduction 2A:—

Fairy Tales

-

Next Page

- Fairy Tales and Pride and

Prejudice:—

Not Cinderella

— The fate of

Narcissus can be

understood as a simple narrative, as a small morality

tale on the dangers of loving oneself so thoroughly that

we become fixated on our reflected glory to the exclusion

of everything else, or as an analytic tool to describe

the workings of a severe neurotic disorder, depending

upon the capacity for intellectual sublety on the part of

the reader.

— The fate of

Narcissus can be

understood as a simple narrative, as a small morality

tale on the dangers of loving oneself so thoroughly that

we become fixated on our reflected glory to the exclusion

of everything else, or as an analytic tool to describe

the workings of a severe neurotic disorder, depending

upon the capacity for intellectual sublety on the part of

the reader.