A man will tell you that the plot of all three literary works discussed in this section — that is to say, English Novel, Norwegian Fairy Tale and Roman Myth — can be summed up in nine words:—

Women's minds work in more subtle fashion. We understand that reducing these three stories to their essence requires discerning seven necessary plot elements:—

It`s in these consequential passages that we realize not only the similarities of structure between Fairy Tale, Novel, and Myth, but how beautifuly and successfully each has been made to differ from the others within an identical artistic framework. As with all great literary creations, plot has been driven by character.

In the previous section Amor and Psyche, (relying on the website http://www.euphoniusmonks.com/amor.htm), Lucius Apuleius's main concern is the narration of the first five elements of the plot. With the death of Psyche's wicked sisters, the story loses much of its charming directness, the emphasis now shifting to the two final plot elements comprised in Psyche's journey and the preordained satisfactory resolution. (Whether this resolution is truly satisfactory will depend on a capacity for the enjoyment of satire on the part of the defenceless reader.)

Because Apuleius's relentless and subversive mockery is aimed not at the immortal inhabitants of Mount Olympus, nor even at his Roman hosts. Ultimately, he's laughing at us and hoping we'll enjoy the jokes along with him.

* * * * *

It begins with a number of transformations:— Romans (like the Greeks before them) didn't bother with the clutter of disorganized solitary magical creatures like trolls and witches and ogres and white bears and dragons in their stories when they could create a bureaucracy of gods and goddesses, all classifiable by hierarchal importance. Psyche’s appeals for help to the other denizens of the higher regions, for example, are met with the explanation by the most powerful gods and goddesses of heaven and the underworld that Venus ranks too highly to be cheated of the jealous game she is embarked upon.

Ceres refuses assistance on the grounds that she may not quarrel with a kinswoman, while Juno protests that she may not give aid against the will of Venus, her son’s wife, whom she has ever loved as a daughter:

... Moreover, I am prevented by the laws forbidding harborage to others' runaway slaves, save only with their master's consent.

Who knew the almighty and all-powerful deities were subject to such worldly restrictions?

And so the unfortunate and blameless Psyche is dragged in front of Venus, who attempts to kill her by assigning impossible tasks to be attempted in circumstances that will certainly prove fatal to a mortal.

Meanwhile a groaning Amor, still suffering from the burn caused by hot oil inadvertently spilled upon him by the deluded Psyche ...

... was kept under close ward in the inner part of the house within the four walls of his own chamber, partly that he might not inflame his wound by the perversity of his wanton passions, partly that he might not meet his beloved. And so those two lovers dragged out the night of woe beneath the same roof, but sundered and apart.

Psyche is assisted not by the gods but by a group of ants, some green reeds, a great bird, and a talking tower.

That last is another of Apuleius's jokes —

Venus feels that she has lost some of her beauty as a

result of all the stressful events taking place and sends

Psyche to fetch for Venus from the Queen of the Underworld

a little of the latter's beauty. In despair Psyche

climbs to the top of the tower intending to cast herself

into the void and be done with it, but is dissuaded by

the talking tower, who gives her a number of rules for

safe passage to the Underworld (including crossing the

River Styx).

The Queen of the Underworld obligingly places some of her beauty in a Golden Box for delivery by Psyche to Venus. Once safely back on earth Psyche can't resist opening the container intending to take just a little for herself. What is the secret of beauty contained in the Golden Box? Sleep! — too much of which escapes and overpowers Psyche until her escaped husband Cupid flies to her, wipes the sleep from her face, puts it back in the box, and sends her on her way.

Cupid then appeals for justice to the great god Jove, who convenes a heavenly meeting, threatening a fine of ten thousand pieces to anyone who absents himself — fear of which, Apuleius assures us, causes heaven's theatre promptly to be filled. And so Jove speaks:—

... Gods whose names are written in the Muses’ register, you all know right well, I think, that my own hands have reared the stripling whom you see before you. I have thought it fit at last to set some curb upon the wild passions of his youthful prime. Long enough he has been the daily talk and scandal of all the world for his gallantries and his manifold vices. It is time that he should have no more occasion for his lusts; the wanton spirit of boyhood must be enchained in the fetters of wedlock. He has chosen a maiden, and robbed her of her honor. Let him keep her, let her be his forever, let him enjoy his love and hold Psyche in his arms to all eternity.

A view of marriage to chill the blood, if we didn't know that Apuleius was being funny.

... Then turning to Venus, Jove adds:

... And you, my daughter, be not downcast, and have no fear your son’s marriage with a mortal will shame your lofty rank and lineage. For I will see to it that it shall be no unworthy wedlock, but lawful and in accordance with civil law.

... Then straightway he bids Mercury catch up Psyche and bring her a goblet of ambrosia ...

... Psyche, drink of this and be immortal. Then Amor shall never leave your arms, but your marriage shall endure forever.

* * * * *

I defy anyone to recount the story of Amor and Psyche using the Greek goddess Aphrodite in the place of Apuleius's vengeful tormenting Venus. Flighty, feckless, faithless Aphrodite, goddess of love and benevolent friend to lovers — surely the last, well, person, to criticize blameless Psyche, even if the god involved should turn out to be one of Aphrodite's adulterously conceived male offspring.

In fact, the Venus/Psyche plot is entirely wrong. It's Jove's wife Juno (formerly the Greek Hera) who plays the relentless female persecutor of mostly innocent maidens taken by force by lecherous husband Jupiter, Jove, or Zeus as the case may be. Changing the avenging fury from wronged wife to mother-in-law from hell destroys the powerful mythic metaphor of society blaming the female in cases of male infidelity.

As for Cupid, little winged infant cherub taking the place of the dark and dangerous Eros, Greek god of adult lust and sensuality, of wild hopeless passionate longing — what is there to say? It appears to me that Apuleius is mocking the Romans' preference for the tamer childish version, too young to understand the implications of wounding by his arrows and thus safely to be blamed for all slips of virtue on the part of mortals and immortals alike. [The original of the bust of Cupid at the right is dated 100 A.D., just before the birth of Apuleius in 124 A.D. and well past the amoral days of the glory that was Greece.]

In seafaring nations such as Greece, Norway, and even Britain, a man is not around long enough to be domesticated to a woman's purposes, and their societies remain resolutely patriarchal. Rome, massively landbased, must have become a matriarchy almost by default, and this attribute shows up unmistakably in Amor and Psyche, the story of an implicit undeclared duel to the death between the two female protagonists, one of whom is immortal and fears not death, but being supplanted in beauty by the younger woman.

* * * * *

Apuleius's depiction of Venus bears more than slight resemblance to Jane Austen's merciless skewering of Lady Catherine de Bourgh. In both instances of Myth and English Novel it's the contrast between the expected attributes and behaviour of subject (all-too-human Roman gods and goddesses; far-from-noble in-thought-and-word-and-deed English landed gentry) that favours us with such involuntary pleasure. To say more surely would be to offer less.

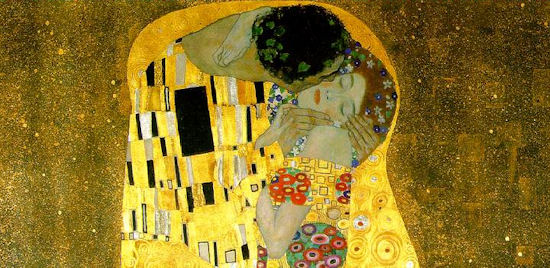

[My choice of Klimt's The Kiss as illustration above is entirely based upon the insights offered on that troubling painting in the BBC TV Private Life of a Masterpiece series.]

________________________