Hansel and Gretel, Carl Offterdinger

Introduction 2A — Fairy Tales

The Source of all* Storytelling

(*All,except Myth.)

My excuse is that

I was raised by grandparents from Northern England.

I can still remember snuggling close to my grandma in the

big soft white bed upstairs in the house in Lachine that

exists now only in memory, while she read a story from the

large thick book of Fairy Tales. Meanwhile my grandad

would busy himself with this, and with that, but possibly

he was listening, too.

Parents, I think, have

a much more businesslike attitude to child

rearing, preferring to make clear from an early age the

difference between fantasy and reality:

grandparents, bless them, realize that their duty

lies in protecting grandchildren from the crass

exigencies of what is perceived to be real, and in

feeding them a diet of Fairy Tales for as long as the

child is hungry for such nourishment.

Fairy Tales exist

to introduce us to ourselves, to acquaint us

with our nature, our reality as small unique persons.

And grandparents remember what parents have chosen

to forget: that without storytelling, there is no

reality. And that all storytelling is based either

upon Fairy Tale, or upon Myth,

its ultimate intellectual fulfilment.

In order to qualify

as a Fairy Tale according to

my highly unscientific system of definition, a story

must comprise a number of inescapable elements:—

- A Journey: There's no sitting

around in Fairy Tales. The

hero or heroine of the Fairy Tale story is embarked upon a

special Once upon a lifetime journey,

a bewildering travel from a time before time through a

process of eternal becoming, of continuous change, to a

completion and culmination of All living

happily ever after in a world without the

infernal demands of incessant alteration;

- Aloneness: There's no team spirit in

Fairy Tales. With the noteworthy exception of the brother and sister

combination in Hansel and Gretel, the protagonist of a Fairy

Tale always walks through life alone. And

so we have been given the companionship of Fairy

Tales, to guide and protect us along the way.

- Uniqueness of Character: There's no need

for identity in Fairy Tales. Heroes and heroines may have names to suit

their situations: Cinderella,

for example, or Sleeping

Beauty, and are often described by

birth order (usually youngest). They are

nevertheless unique by virtue of their circumstances and

the detail which surrounds each story.

- Resistance to Change: There's no growing

up in Fairy Tales. At the end of the Fairy Tale

Journey, the circumstances of the protagonists have

changed, always for the better (and heartbreakingly often

the fruits of this good fortune are shared with the

families that have rejected them). But the hero or

heroine is necessarily unaltered — necessarily

because with so much change all about, we need the

constancy of Fairy Tales to

reassure us that we are unalterable in our essential

nature;

- Strangers along the route: There's no

lack of company on the road in Fairy Tales. Another common

element is the journeying child encountering helpful strangers along the route.

(The occasional stranger will hinder, or torment,

rather than assist, depending upon the vagaries of the

plot.) Like everything else in a child's

world, the strangers appear suddenly and inexplicably,

and disappear forever once their essential role has been

played out.

- Creatures with magical powers: There's

no need for fairies in Fairy Tales. No need for fairies, but

the presence of magical creatures such as witches, ogres, dragons, and

trolls is awaited with expectant pleasure in any Fairy

Tale worthy of the name.

- Detail: There's no Fairy Tale without

detail. And that means a wealth of detail, distinctive and

distinctly unsettling detail forming an iridescent backdrop to the

pageant of the obligatory journey, each Fairy

Tale possessing its own unique and

inseparable, unvarying and inexplicable store of features

to pique and burrow into the imagination. Detail

such as:—

- — A troop of unsuccessful suitors and their

horses thrashing

about unable to halt their inexorable downward

slide toward a gruesome death at the foot of the

glass mountain (The

Princess on the Glass Mountain;)

- — A dog with a sleeping Princess on his back

loping through the midnight streets on the way

to a meeting with a waiting stranger (The Soldier

and the Tinder Box;)

- — A head of hair so thick and so strong that

a witch (and later a handsome prince) is able to

climb up and join Rapunzel

in her tower (and, in the same tale, a wife

sickening almost unto death of unappeasable

hunger for the similarly-named salad green

rapunzel growing in the garden of the next-door

neighbour, who happens to be a witch);

- — A golden harp which calls out for help to

its master when it is being stolen by the

marauding Jack of Jack

and the Beanstalk fame (as well

as a hen that lays golden eggs — both

items purloined from a giant that eats

little boys for breakfast).

- Truthfulness:

There's no lying in Fairy Tales. Children

hearing a Fairy Tale have no reason to doubt its essential

truthfulness. They understand instinctively that

the purpose of a Fairy Tale is to reconcile them to their

own natures, and for that reason the story must be recounted

over and over without alteration.

- Humour and irony: There's no irony in

Fairy Tales. There may be, however, a

great deal of humour.

- Innocent amorality: There's no right

and wrong in Fairy Tales. Fairy

Tales are marked by an innocent amorality,

particularly as regards taking what you want because it's

there and you want it.

- Tolerance:

There's no preaching in Fairy Tales.

Things happen in Fairy Tales

because they happen, and the protagonist of the piece

does what he or she must because that's how things

happen. Drawing a lesson is pointless.

- Subterranean Meaning: There's no

explanation in Fairy Tales. None given. None

needed. Each child extracts his or her own essential meaning from

hearing and reading a Fairy Tale

over and over. No one else can ever enter into the

child's comprehension of what is heard, and read, and

understood — which

is probably just as well.

In conclusion.

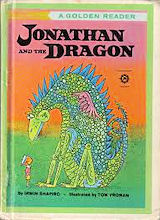

When my son was very little, his favourite book

was Jonathan

and the Dragon, a modern (1962) American

Fairy Tale, in verse yet, by

Irwin

Shapiro. Library rules

allowed us to keep a book for two weeks after checkout,

with the possibility of renewal for an additional two

weeks unless specifically requested by someone else.

One day the unthinkable happened. Months went

by, and the book was not returned.

After meeting his worried eyes one time too many at bedtime, I

bought my son the book. In hard cover. Complete with dust

jacket.

There are many stories about a hero slaying the dragon.

And some stories where the dragon is outwitted.

But Jonathan chose a different way. To the

consternation of the assembled mayor and townspeople,

Jonathan walked up to the dragon — who had previously

been shot at with a ball from a cannon that bounced off his

head, and fed a toxic soup which he gulped down with obvious

enjoyment — and whispered in this

uninvited guest's ear a polite request that he depart

forthwith. Naturally the dragon complied.

. . .

He stood up slowly, as a dragon must

He walked away in a cloud of dust.

Everyone shouted, Hurrah, Hurray!

For Jonathan has saved the day!

My son was only a small boy, seemingly ready to be formed by

school, church, and societal pressures. But could

it be that already he was in touch with the man he

has become:— friendly, tolerant, and direct;

inventive, independent, and resourceful?

If it's true that Fairy Tales

introduce us to ourselves, and, by virtue of hearing them

over and over, acquaint us with our natures, it seems

obvious that having them read to us gives us the security

of a stamp of approval, as if the world has produced

these unique stories particularly for our

edification. Of course some Fairy

Tales have been sanitized into a state of

cuddly incoherence, but pain, suffering and unimaginable

cruelty are the mainstays of the authentic original

versions, with no correlation between deservingness and

punishment, worthiness and reward.

Outside in the real world, all is frightening uncertainty.

Inside, in the safety of a story told by a truthful

reader to a trusting listener, is the warmth of the

unspoken consolations of the wisdom of the ages.

Next we move on to Fairy Tale's

grownup sophisticated cousin. I refer, of course,

to Myth, and stories we read for ourselves,

rather than having

them read to us.

[June 2007, text only

WebPage last amended

February 20th, 2013]

________________________

-

Top of this Page

- Introduction 2A:— Fairy Tales

-

Main Page – Index

- Main Page – Index

-

HomePage-2

- HomePage-2

Fairy Tale and Myth

-

Previous Page

- HomePage-2

Fairy Tale and Myth

-

Next Page

- Introduction 2B:—

Myth