It is the nature of romantic comedies to lend themselves to plots involving benevolent impersonation, the act of persuading an accommodating stranger to carry out the exigencies of the plot:—

To show up on the blind date. To write the exam. To meet the employer/future mother-in-law. To play the husband, the lover, the father, the girlfriend. To sing the ballad/recite the poetry under the lovely lady's window. To pretend to be straight — or gay. Since Shakespeare's time each elaborate charade exists as a means for the artistic creators to bring the lovers to a predestined conjoined future, the particular details of auxiliary personages and plot being thrown in for comedic relief.

And because the person chosen to carry out the imposture by definition is perfect for the role (The Stranger in Dear Frankie being the obvious example), we wait with anticipation and pleasure for the romantic comedy plot to resolve itself as pretext evolves into predictable reality.

Except that Dear Frankie isn't predictable. Isn't romantic. Isn't comedy.

And there's no sense sitting there assuming that with sufficient force of character we can will the closing scenes to give us what we want. They cannot — for the simple reason that a classic love story such as Pride and Prejudice as well as successful romantic comedies like Working Girl and Pretty Woman end at the precise moment when the lovers are truly equal, which is to say that the heroine answers the needs of the hero as well as the other way round.

What, then, of The Stranger in Dear Frankie, a man who not only serves the plot, but is the plot? How can there be any notion of equality with a man chosen specifically as having no past, no present, and no future?

No doubt but that Dear Frankie is unsettling rather than enjoyable the first time around. Almost from the beginning it becomes obvious that we are watching something other than a fairy tale journey from small town to big city, from poverty to unimaginable riches, from unhappiness to a problem-free future. And yet the story lacks the permanence that signals the presence of implacable myth, showing instead unmistakable opportunities for change, for growth. Lizzie Morrison is every parent whose own life is parched desert, but who has nevertheless created an oasis of verdant possibilities for her child. In Myth the child would be a helpless pawn, a type rather than Dear Frankie's fully realized individual, utterly resilient, and in charge of his fate.

We can tell ourselves that the film lacks any purpose and it's time to move on to the next thing, or back to a previous comforting thing, only to find our minds reverting to Dear Frankie as a piece of unfinished business. Do we watch Dear Frankie with such resentful eyes precisely because of its timeless quality, our feeling that we are seeing the updating of a very old story? But if not modern fairy tale, or myth, then what, exactly?

. . . . .

In emotional tone we might almost be assisting at malevolent impersonation, seldom to be found in the pure comedic niche: variations on the story of Jacob impersonating Esau in order to steal his birthright have been treated since biblical times almost always for their potential impact as mysteries or action thrillers. The best such Novel (and subsequent 1986 BBC 3-part miniseries) on our bookshelves and VCR collection is Josephine Tey's 1949 Brat Farrar, another assemblage of strongly marked characters soaring high above its theme.

And yet nothing could be more benevolent — on the surface at any rate — than Dear Frankie's Lizzie Morrison creating a fictional father who has left the family voluntarily for a life at sea, and this to take the place of the husband she is actually fleeing.

http://ww3.tvo.org/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brat_Farrar

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0090401/reviews [bbc miniseries also see youtube in favourites]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pride_and_Prejudice

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pretty_Woman

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Working_Girl

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Private_Life_of_a_Masterpiece

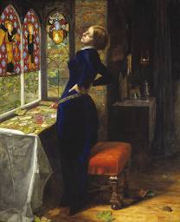

Thank heaven for TV Ontario (TVO) which presents a wealth of British programming including the BBC television series The Private Life of a Masterpiece. Most of the objections to Dear Frankie ring with eerie familiarity in the ears of viewers of that magnificent series:— Van Gogh's Sunflowers. Michaelangelo's David, Munch's The Scream, Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe. Each placed under intense informed professional observation, revealing unsuspected psychological truths that demolished conventional belief. And each loathed vociferously by the shapers of its era's conventional beliefs. By the time we got to Vermeer's The Art of Painting, and Klimt's The Kiss, even an artistic philistine was forced to the realization that every masterpiece has one quality in common. Each is unique.

Which brings us to Edgar Dégas's uncharacteristic sculpture La petite danseuse agée de quatorze ans — in English The Little Dancer Aged Fourteen.

Perhaps today it would be less shocking that the sculpture is wearing an actual tutu on her body as well as a red ribbon in her hair. — Although the statue's placement in a glass box might give even today's gallery clients the odd qualm. In fact Dégas seemed to delight in leaving viewers of his work grappling with baffled irritation.

I once went into an unfamiliar photography shop to pick up some photos for an employer — and came back to work an hour late. All around that shop were hughly enlarged black-and-white shots of ballet dancers, performing singly and in pairs and groups. At that point in my word-bound existence, dance was no more than keeping time to music. I had no idea that ballet was composed of light and shadow, lines and planes and relationships and alignments, unseen, unsuspected, an outflung arm here balanced and echoed by a demurely placed toe over there. And all at such speed that only an artist's eye could capture and display the momentary magic.

And yet Dégas, whose numerous drawings and paintings showed female dancers in various poses, almost never depicted them engaged in the actual dance. The determinedly raised chin of his Little Dancer leads to the suspicion that he saw his models not as pretty objects but rather as hard-working actors arduously training their bodies as techical components of an intricate machine; and doubtless he had his valid artistic reasons a century ago for showing his dancers in every aspect of their professional existence other than engaged in the thrilling leaps of escape from the restrictions of gravity and inertia that have fascinated watchers since dance was invented, just as the artistic creators of Dear Frankie have theirs today in denying their characters — and us — the enchantment of a fairy tale ending. Or beginning. Or middle.

I have permitted myself the extravagance of comparing the two only because both seem to demonstrate no small degree of admiration for their subjects — that phenomenon of esteem that I find so irresistibly seductive.

________________________